Antimicrobial and Antibiotic Resistance in Beef Cattle

Antimicrobial resistance occurs naturally when the genetic make-up of microbes is altered in a manner that makes them no longer susceptible to antimicrobials designed to kill them or prevent their growth. In Canada, surveillance indicates that the prevalence of resistance in cattle varies depending on the bacteria and the antimicrobial drug. Research and surveillance evidence suggest that eliminating antimicrobial use in beef production would have clear negative health consequences for cattle while the benefit for human health is unclear.

Definitions

Antimicrobial: a substance that can destroy or prevent the growth of microorganisms. There are many different types of antimicrobial substances, including antibiotics, anti-protozoals (e.g. ionophores for coccidiosis), biocides like alcohol, soap and bleach.

Antibiotic: an antimicrobial substance produced by a microorganism (or a synthetic version) that can kill or prevent the growth of another microorganism. In human and veterinary medicine, antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections.

All antibiotics are antimicrobials, but not all antimicrobials are antibiotics. The two terms are often used interchangeably.

Medically Important Antimicrobial: Antimicrobials considered to be important for the treatment of bacterial infections in humans.

Drugs that are essential for the treatment of serious bacterial infections in humans are considered more important. Resistance development against those antimicrobials might have more serious consequences for human health, particularly if there is no or limited availability of alternative antimicrobials for treatment.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Antimicrobials used in Canadian beef production are regulated by Health Canada |

| Medically Important Antimicrobials used in Canadian beef production are only available by prescription in the context of a valid Veterinary-Client-Patient Relationship (VCPR) |

| Antimicrobial resistance is a natural phenomenon |

| Antimicrobial use doesn’t cause antimicrobial resistance, but it can speed up the rate at which antimicrobial resistance develops. Good antimicrobial stewardship helps limit selection for antimicrobial resistance, prolonging the effectiveness of antimicrobials |

| Responsible antimicrobial use in cattle is critically important to make sure antimicrobials continue to be effective in treating illness in both cattle and humans. |

| When antimicrobial use is measured in milligrams of active ingredient per kilogram of animal biomass, drugs belonging to Low Importance category (Category IV), such as ionophores, account for approximately half of antimicrobial use in Canadian beef production. Ionophores are not considered to be medically important in human medicine by the World Health Organization |

| Although Medically Important Antimicrobials are used, Category 1 antimicrobials (classified as “very high importance to human medicine”) are a very small proportion the antimicrobials used in Canadian beef production |

| Medically Important Antimicrobials approved for use in beef cattle are only available under veterinary prescription and cannot be used to improve growth or feed efficiency |

| Antimicrobial use, resistance and alternatives are the focus of a great deal of research effort in Canada’s beef industry |

| The Public Health Agency of Canada conducts antimicrobial use surveillance in Canadian beef feedlots, as well as antimicrobial resistance surveillance in feedlots, abattoirs and retail beef through the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS). |

Introduction to Antimicrobials and Antibiotics for Beef Cattle

Antimicrobials are used in aquaculture, fruit production, beekeeping, livestock production, pets, wildlife, some crops, industrial and household chemicals and human medicine. In livestock, various categories of Medically Important Antimicrobials are used for therapy (i.e. treat illness) or disease control. The use of Medically Important Antimicrobials for production purposes in livestock (i.e. improve feed efficiency) has been banned in Canada1. Other management tools used to prevent and control disease in beef production include vaccines, nutrition, hygiene, housing and anti-parasitics.

Video: What Beef Producers Need to Know about Antimicrobial Use and Resistance

Function of Antimicrobials

Nearly all antimicrobials are natural or synthetic versions of antimicrobials naturally produced by soil microorganisms. When two types of microbes share the same environment and rely on the same nutrient source to exist, microbe A will have a competitive advantage if it can produce and excrete an antimicrobial that inhibits or kills microbe B and vice-versa. At the same time, microbe A will have naturally evolved a resistance mechanism to protect itself against its own antimicrobial so that it doesn’t accidentally kill itself – this is called “intrinsic resistance”.

Antimicrobials are used in human and veterinary medicine for the same reasons. Using an antimicrobial to target specific microbial pathogens is an effective way to combat infectious disease, especially when effective vaccines are not available.

Antimicrobials harm or kill their target microbe by damaging or blocking specific structural features (e.g., the cell wall or a cell surface receptor) or metabolic functions. Sometimes target microbes undergo random genetic mutations or acquire resistance genes from another (resistant) microbe. This can change structural features or metabolic processes that make the target microbe and its offspring resistant to that antimicrobial (or related antimicrobials that kill or prevent growth in the same manner).

How Antimicrobial Resistance Develops

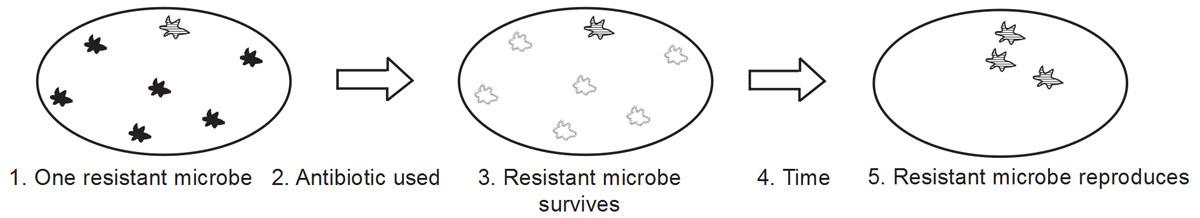

Antimicrobial resistance occurs naturally and is not caused by antimicrobial use. If the antimicrobial is used when an antimicrobial resistant disease-causing microbe (pathogen) is present, the antimicrobial resistant pathogen will have a competitive advantage over its susceptible cousins. Though antimicrobial use does not cause antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial use does select for antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial use does not cause antimicrobial resistance

If the antimicrobial continues to be used, the resistant pathogens will survive, reproduce and become more common, while the susceptible pathogens will gradually become more scarce. In this case, the antimicrobial will become less effective and the animal will not respond to continued treatment with the same antimicrobial, even if the dose is increased. In response, the veterinarian or doctor may switch to an antimicrobial from a different class or category.

Categories of Antimicrobials

Antimicrobials are divided into four categories based on their importance in human medicine2,3. Each category of importance contains antimicrobial drugs of different classes. Classes of drugs are based on their chemical makeup and mechanism of action.

- Category I: Antimicrobials classified as ‘Very High Importance’ are used to treat very serious bacterial human infections and there are limited or no alternative antimicrobials for effective treatment.

- Category II: ‘High Importance’ antimicrobials are of intermediate concern in human medicine and have generally effective alternatives available.

- Category III: ‘Medium Importance’ drugs are rarely used to treat serious human health issues. For example, tetracycline used to treat acne is classified as Medium Importance.

- Category IV: Antimicrobials of ‘Low Importance’, like ionophores, are not used in human medicine to treat bacterial infections.

In Canada, Medically Important Antimicrobials include those in the Very High, High and Medium Importance categories. Low Importance Antimicrobials are not classified as Medically Important. Antimicrobials from all four categories (Low, Medium, High or Very High importance) are registered for use in beef cattle in Canada. When antimicrobial use is measured in milligrams of active ingredient per kilogram of animal biomass, drugs belonging to Low Importance category (Category IV), such as ionophores, account for approximately half of antimicrobial use. Using the same metric, drugs of Medium Importance (Category III) account for most (70-80%) of the Medically Important Antimicrobial doses used in Canadian beef cattle.

Antimicrobials of Low importance include ionophores, which are used in beef cattle to prevent diseases such as coccidiosis and to improve feed efficiency2. Generally, Category II and III antimicrobials are used for treatment or control of bacterial infections. In Canada, Category I antimicrobials (Very High importance) are seldom used in beef cattle production and only for treatment (not control or prevention) of severe bacterial infections in overtly sick animals.

| Category of Importance in Human Medicine |

Antimicrobial Class | Brand Names of Antimicrobial Products Registered for Use in Beef Cattle in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| I: Very High | e.g. fluoroquinolones | e.g. Baytil, A180, Forcyl |

| e.g. 3rd/4th generation cephalosporins | e.g. Excenel, Excede, Cevaxel, Eficur, Ceftiofur | |

| II: High | e.g. macrolides | e.g. Tylan, Micotil, Draxxin, Zuprevo, Zactran, Increxxa, Lydaxx, Macrosyn, Rexxolide, Tulaven, Tilinovet, Tulissin |

| III: Medium | e.g. tetracyclinese

e.g. phenicols |

e.g. Liquamycin, Aureomycin

e.g. Nuflor, Resflor, Fenicyl, Florkem, Zeleris |

| IV: Low | e.g. ionophores | e.g. Rumensin, Bovatec, Posistec, Avatec, Coban, Kexxtone, Monensin, Monovet |

Concerns in Public Health

Many antimicrobial classes that are used in livestock are also used in human medicine. The potential risk of antimicrobial resistance in humans owing to antimicrobial use in veterinary and other settings in an important public health concern that we are seeking to better understand. The greatest concern is with antimicrobials that are of Very High Importance in human medicine and are also used in livestock. These are drugs of last resort in human medicine (and in veterinary medicine); they are used for infections that are not responding to lesser drugs and for which there are no other alternatives. If the Very High Importance drugs fail to work, doctors (and veterinarians) have no other options.

The use of all antimicrobials in veterinary medicine are approved and regulated by Health Canada.

Ionophores (classified as ‘Low Importance’ in human medicine) are often erroneously included in discussions about the concern of antimicrobial use in livestock and the potential link to antimicrobial resistance in humans. Ionophores are not used to treat bacterial infections in human medicine and have a very different mode of action than antibiotics. At present, there is no strong evidence that ionophore use leads to cross-resistance to antibiotics of importance in human medicine.

Producers work with their veterinarians to develop protocols on when it’s appropriate to use various antimicrobials, and adhere to withdrawal times to ensure treated animals do not enter the food system until it’s safe to do so.

The potential link between antimicrobial use in cattle production and antimicrobial resistance in human medicine has been very difficult to prove or disprove. One study funded by the Canada-Alberta Beef Industry Development Fund found that bacteria isolated from feedlot staff who worked both with sick cattle and the drugs themselves had antimicrobial resistance levels that were no higher (and were lower in many cases) than in bacteria collected from human health labs.

The Canadian beef industry has supported a number of research projects studying this issue since the late 1990’s. Two studies funded through the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) have found that drugs that are most important for human health are rarely used by the Canadian beef industry. Conversely, the Low Importance antimicrobials that are used most widely by the Canadian beef industry are not used to treat bacterial infections in human medicine.

Most recently, research supported through the Beef Science Cluster has examined the risk that antimicrobial residues, resistant bacteria or resistance genes can travel from feedlot environments to human environments through manure, soil and water. This study found that composting manure is an effective way to dissipate antimicrobial residues and resistance genes. Furthermore, wetlands and microbiologically active soils play an important role in degrading antimicrobials and resistance genes. Consequently, microbial populations and antimicrobial resistance profiles from feedlot and human associated environments differ significantly.

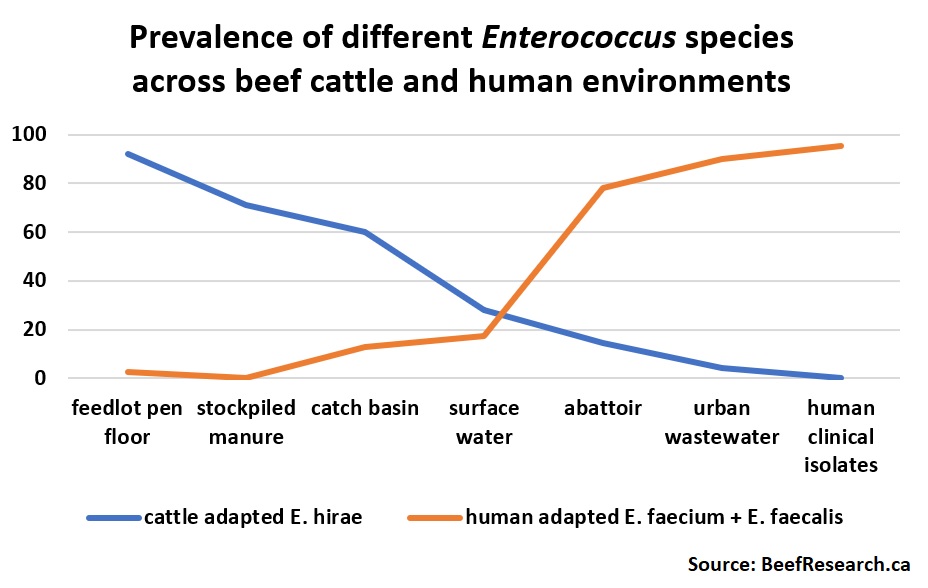

Bacteria that have adapted to thrive in one particular environment often won’t be able to compete with their close relatives who have adapted to thrive in a different environment. For instance, Enterococci are a group of bacteria that are commonly found in both cattle and humans. However, there are many, many different kinds of Enterococci, each with their own preferred environmental niche(s). Enterococcus hirae are the most common Enterococcus in beef feedlot cattle (and rarely found in humans), while Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are commonly found in humans but are rarely found in feedlot cattle. Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis are the enterococci that most often cause infections in humans.

Even when E. faecium and E. faecalis were occasionally found in cattle, their genetic makeup and antimicrobial resistance patterns differed from the E. faecium and E. faecalis found in human patients. The E. faecium and E. faecalis occasionally found in cattle also lacked the genes required to induce illness in people. This strongly suggests that antimicrobial use practices in beef production influence antimicrobial resistance patterns in cattle-associated environments, while antimicrobial use practices in human medicine influence antimicrobial resistance patterns in humans.

One feedlot in the study raised some pens of cattle using antibiotics (“conventional production”) and raised other pens of cattle without antibiotics (“natural production”). The same types of antibiotic resistance genes were found in both conventional and natural pens. However, a larger total number of antibiotic resistance genes were found in the conventional pens. This underscores the fact that the more antibiotics are used, the more common antibiotic resistant bacteria will be found in cattle. This means that responsible antibiotic use in cattle is critically important to make sure antimicrobials continue to be effective in treating cattle illness, even if it doesn’t pose a downstream risk to human health. The observation that resistance genes were still detected in bacteria from the pens with no antimicrobial use underscores that using antibiotics does not result in only bacteria without antimicrobial resistant genes, again emphasizing that antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon.

Concerns in Cattle Production

Antimicrobial resistance is a concern in livestock production for two reasons:

- If pathogens develop resistance, antimicrobials won’t work as effectively, animals will not respond to treatment as strongly and the risk of animal health and welfare concerns and death may increase.

- Antimicrobial resistant livestock pathogens may be able to pass their resistance on to human pathogens. This would result in antimicrobial drugs not being as effective in treating human infections as well

Research is ongoing to explore antimicrobial resistance in beef cattle. There are potential economic penalties to consider when reducing antibiotic use, such as increased illness and death loss. Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is very contagious particularly when new calves enter the feedlot. The contagious spread of resistant BRD pathogens among animals is primarily responsible for the widespread BRD early in the feeding period. The connection between BRD incidence in cattle and resistant BRD pathogens supports concern that antibiotic use leads to reduced antibiotic effectiveness in cattle.

Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Beef Cattle

The Canadian Feedlot Antimicrobial Use (AMU) and Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Surveillance Program (CFAASP) is a collaborative effort between the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) and the Canadian beef industry. In addition to this project, CIPARS also monitors antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock (including cattle in feedlots and at slaughter plants) and retail meat.

CFAASP monitors antimicrobial resistance in both enteric organisms with relevance for human health (Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Enterococcus spp.) and in respiratory pathogens with relevance for cattle health (Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni). Surveillance indicates that the prevalence of resistance in feedlot cattle varies depending on the bacterial organism and the antimicrobial drug.

Surveillance results fluctuate from year to year but CIPARS results to date indicate that antimicrobial resistance is relatively low to antibiotics of high and very high importance in human medicine. Multidrug resistance is low for many pathogens but remain a concern for Pasturella multocida and Enterococcus species.

Research and surveillance evidence suggests that eliminating antimicrobial use in beef production will have clear negative health consequences for cattle with no obvious benefit for human health.

Building on antimicrobial use and resistance surveillance frameworks developed in collaboration with the beef industry, CIPARS has implemented an Alberta feedlot component to its on-farm surveillance programs in 2016. In 2019 this pilot was expanded; surveillance across Canada is ongoing through CIPARS and related projects.

While much of the antimicrobial use and resistance research in beef cattle has focused on the feedlot sector, antimicrobial use has also been studied in Canada’s cow-calf sector. A survey of 100 cow-calf operations enrolled in the Canadian Cow-Calf Surveillance Network found that while Medically Important Antimicrobials were used nearly all herds, most were Category III (Medium Importance) antimicrobials, and were used in fewer than 5% of cows, calves or bulls in most herds. Lower antimicrobial use in cow-calf herds (compared to feedlots) likely results from a lower disease challenge related to lower stress, less co-mingling of animals from multiple sources, and a lower stocking density on pasture compared to confinement pens. Since the implementation of a required veterinary prescription for antibiotics in 2018, there have been very minimal changes to antibiotic use practices on cow-calf farms. Research has found that antibiotic resistant bacteria were extremely uncommon in beef calves sampled at or near weaning. Surveillance of antimicrobial use and resistance in cow-calf herds is continuing through the Canadian Cow-Calf Health and Productivity Enhancement Network.

Important Facts about Antimicrobial Use in Beef Cattle Production

Livestock industries are also often criticized due to misinformation and misunderstanding around the availability and use of antimicrobials in livestock production.

Prescription Only

In simple terms, A VCPR means that your veterinarian understands your operation, your management practices, your herd, and common health issues well enough to provide meaningful advice and oversight

In Canada, cattle producers cannot purchase Medically Important Antimicrobials over-the-counter. They are only available by veterinary prescription, within the confines of a valid veterinary-client-patient relationship (VCPR).

Antimicrobials in cattle feed

Medically Important Antimicrobials cannot be labelled or used for growth promotion of cattle in Canada1. A veterinary prescription is required before feed containing Medically Important Antimicrobials can be formulated and sold.

The method of antimicrobial delivery may be confused with the purpose of use. In-feed antimicrobials are used to control and prevent important feedlot diseases and are not used to promote growth. Instead, if a large number of animals need to be treated on a daily basis for a longer period, it is much safer and less stressful for the animals to deliver the antimicrobial through feed or water than to handle each individual repeatedly for daily injections.

Water or feed may be used to deliver oxytetracycline and chlortetracycline to feeder calves at high risk of respiratory disease. Similarly, oral tetracycline may be prescribed to teenagers to treat acne, not to make them grow faster.

A poor appetite is a common sign of respiratory disease in cattle. Keeping animals healthy keeps them eating and growing, which may also contribute to the confusion between antimicrobial use for health purposes and growth promotion. However, giving antimicrobials to healthy cattle does not improve growth rate or feed efficiency.

Using antimicrobials to control disease

Metaphylaxis is the treatment of a group of animals to combat a disease outbreak or to control the spread of infection when the risk of developing disease is high. This strategy may be used to prevent respiratory disease in high-risk (lightweight, freshly-weaned, auction mart derived) calves. Newly arrived feedlot calves may be stressed, depending on whether they have been recently weaned, how far they have been transported weather conditions, and whether they have been adapted to dry feed. Stress can impair immune function. Since effective vaccines are not available for all of the respiratory pathogens and because vaccines are less effective if they are administered when cattle are stressed or after they have already started to develop signs of illness, antimicrobials may be used to control the development and spread of disease for the first few weeks in the feedlot. Once the calves have adapted and overcome the initial stressors, the incidence of disease is much lower.

Use of Medium or Low Importance antimicrobials to effectively control or prevent disease in cattle can reduce the need to use more powerful antimicrobial drugs of High or Very High Importance to treat and cure disease once the disease has progressed and become more serious.

Using antibiotics on animals with viral infections

Viruses are not susceptible to antibiotics. An antibiotic will not be effective against calf scours caused by rotavirus or coronavirus or respiratory diseases caused by viruses (e.g. BVD, IBR, PI-3, BRSV). However, calves with neonatal diarrhea initiated by viruses but with evidence of secondary bacterial infections can also require treatment with antibiotics. Similarly, respiratory disease initiated by a virus may be treated with antibiotics to reduce the significant risk of secondary bacterial infections that can result in pneumonia and sometimes death in calves if left untreated. Work with a veterinarian to accurately diagnose illnesses in cattle and provide effective treatment.

Viruses are not susceptible to antibiotics.

Monitoring the amount administered

Modern cattle feeding operations and feed mills are equipped with highly sophisticated feed processing, mixing and delivery equipment that help to ensure that each animal receives the amount of antimicrobial needed when delivered through the feed. Injectable antibiotics are delivered even more precisely, with a specific volume given to an animal depending on its individual body weight.

Commercial and on-farm feed mills are under the regulation of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Avoiding Antimicrobial Resistance

The development of antimicrobial resistant microbes can be discouraged through management practices that reduce the need for antimicrobial use, such as nutrition, calving management, preconditioning and vaccination. Prudent use of antimicrobials when necessary will further reduce the development of antimicrobial resistant microbes.

Using Antimicrobials Responsibly

- Monitor cattle health on an ongoing basis to ensure prompt treatment or care.

- Prompt treatment will usually give a better response rate and require fewer treatments

- Delayed treatment can be responsible for treatment failure and then prolonged treatment course as a result

- Delayed treatment will increase the risk of spread of infection

- Monitor effectiveness of treatment so that ineffective treatments are remedied quickly

- Have an accurate diagnosis before using antimicrobials.

- For example, not all lameness is footrot or caused by a bacterial infection

- Viruses are not susceptible to antibiotics

- Antimicrobials that specifically target the pathogen should be selected over broader-spectrum agents and local therapy should be selected over systemic therapy when appropriate

- Choose the right product to treat the condition

- Have a conversation with your veterinarian to help determine whether the health benefit of treatment from a particular antimicrobial drug outweighs the potential risk and burden on resistance

- Follow veterinary and/or label instructions

- Use the proper route of delivery (oral, subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous)

- Deliver the drug in the proper dose

- Administer the drug for the proper number of days

- Treatment should not be stopped earlier than veterinary and/or label instructions indicate as reduced symptoms may be confused with a cure.

- Provided veterinary and/or label instructions are followed, antimicrobials should be used for the shortest time period required to reliably achieve a cure. This minimizes exposure of other bacterial populations to the antimicrobial.

- Consult with your veterinarian, seek out training and use the appropriate drug for the diagnosis when using remote drug delivery devices

- If the product label is no longer available, visit the Compendium of Veterinary Products to search for it.

- Properly dispose of expired product, empty containers and used needles

- Adhere to requirements and recommended procedures in Canada’s Verified Beef Production PlusTM on-farm food safety program

- Know when to euthanize. It is more responsible to euthanize an animal that has a poor prognosis for recovery than to treat it with antibiotics. Use acceptable procedures and equipment for euthanizing cattle as stated in the Beef Cattle Code of Practice.

Preventing Illness to Reduce the Need to Use Antimicrobials

Reduce stress on animals. Stress can weaken the immune system, increase the risk of disease, and increase the reliance on antimicrobials. Consider practices such as:

- Update vaccination programs

- Vaccination is key to preventing illness and reducing antimicrobial use

- Ensure cattle have an effective immune response to vaccination by following label directions and minimizing stress on the animals

- A veterinarian will help develop a feasible vaccination program, based on the level of risk in the herd. This will cost less than the expense of diseases if they were to occur

- Evaluate the economic opportunity from preconditioning programs with this calculator.

- Consider using low stress weaning methods and performing other stressful activities such as vaccination prior to weaning.

- Ensure adequate nutrition through water and feed quality testing and consult a nutritionist if there are concerns that nutritional needs are not being met

- Maintain as clean and dry of pastures and pens as possible with protection from the elements

- Use biosecurity practices to reduce spread of infection among animals

- Minimize commingling of animals from different sources when possible

- Isolate sick animals

- Avoid overcrowding

- Ensure you have a valid veterinary-client-patient relationship and maintain an ongoing relationship with your veterinarian Gather and share your knowledge and records with your veterinarian, including the history of incoming cattle, to help determine effective disease prevention routines

- Develop and maintain a suitable herd health management program including vaccination and treatment protocols

- Develop and maintain biosecurity protocols to help prevent and contain diseases

- Record the temperatures of sick animals

- Observe and record responses to treatment

Producers who participate in Canada’s Verified Beef Production PlusTM (VBP+) program demonstrate that they follow industry-sanctioned practices which select, use, store and dispose of antimicrobials in a responsible manner.

Antibiotic Alternatives

Research into antibiotic alternatives, such as probiotics, prebiotics, essential oils, enzymes, immune stimulants and more is underway. At this time, there is no evidence to suggest there these products are reliable replacements for antimicrobials. However, there are several key management practices to maintain animal health and reduce the need for antibiotic use, including:

- provide cattle with optimal nutrition throughout the production cycle

- maintain an appropriate vaccination and health management program

- ensure newborn calves receive at least two litres (half a gallon) of high-quality colostrum within two hours of birth

National Beef Antimicrobial Research Strategy

The National Beef Antimicrobial Research Strategy was developed by the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) and the National Beef Value Chain Roundtable (BVCRT) following comprehensive analysis of the antimicrobial research situation relevant to the Canadian beef sector, extensive consultation and validation with all major stakeholder groups and collaboration with funders toward coordinating and aligning funding priorities. This strategy identifies priority research outcomes for the Canadian beef industry and has gained the commitment from Canada’s major research funders to focus on achieving these outcomes.

Research outcomes have been defined in the priority areas of:

- Antimicrobial Resistance,

- Antimicrobial Use, and

- Antimicrobial Alternatives

This strategy continues to guide research priorities and discussion around antimicrobial use and resistance. It has been incorporated into succeeding versions of the Canadian Beef Research and Technology Transfer Strategy.

- References

-

1 Health Canada, 2024. Responsible use of Medically Important Antimicrobials in animals. Available here.

2 Health Canada, 2009. Categorization of antimicrobial drugs based on importance in human medicine. Available here.

3 World Health Organization, 2024. WHO List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: A risk management tool for mitigating antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available here.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Tim McAllister (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Dr. Cheryl Waldner (Western College of Veterinary Medicine), Dr. Sheryl Gow (Public Health Agency of Canada) and Dr. Dana Ramsay (Western College of Veterinary Medicine) for contributing their time and expertise during the development of this page.

This content was last reviewed April 2025.