Anthrax in Beef Cattle

The risk of anthrax is highest after flooding and/or during drought and in alkaline areas.

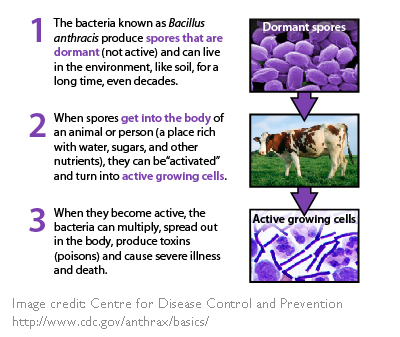

Anthrax is an infectious soil-borne disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, a relatively large spore-forming bacteria that can infect mammals. Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores, particularly bison and beef cattle. Anthrax is not highly contagious (i.e. is not typically passed from animal to animal). Anthrax infections are rare in humans.

| Key Points |

|---|

| The three types of anthrax as gastrointestinal, cutaneous and pulmonary. |

| Disease symptoms only last two to three hours. Therefore the most common sign is sudden death. |

| The best way to prevent the disease is by preventing the production and dispersal of spores. |

| Proper disposal of mortalities helps limit the spread and recurrence of anthrax. The recommended process for disposal of dead cattle that may have contracted anthrax is a 3-step process. |

| Anthrax vaccination is most effective two to three weeks before exposure. Antibiotics can interfere with immunity if administered eight days before or after vaccination. |

Types of Anthrax

Due to anthrax being a soil borne disease, beef cattle and bison are most likely to contract the disease because they graze lower to the ground than many other herbivores, particularly in drought conditions or overgrazed pastures. It is also believed that the abrasive forages they consume can injure the mouth and allow the bacteria quick access to the blood stream.

Three types of anthrax:

- Gastrointestinal: Caused when bacteria spores from an infected animal are ingested. The most common cause of anthrax in beef cattle.

- Cutaneous: Contracted via a skin wound. The most common way that anthrax is contracted by people.

- Pulmonary: Caused when the bacteria are inhaled. This type is the most dangerous, but is virtually impossible for animals to contract under natural conditions. This type of anthrax occurs in rare situations where people are working directly with contaminated hides.

When an animal dies of anthrax, the bacteria is present in most tissues of the body. If the tissues are not exposed to oxygen, the bacteria cannot form the spores that infect other animals, and quickly die off. However, in most cases scavengers or carnivores open the carcass soon after death. This exposes the bacteria to oxygen, allowing infectious spores to form.

Spores are tough, ‘egg-like’ microscopic structures that are difficult to destroy and can survive for decades. Spores continue to live in the soil long after the animal has decomposed, especially in alkaline (non-acidic) soils. Anthrax spores end up deep in the soil and are brought to the surface when the ground is disturbed, for example by:

- digging (wells, ditches, pipelines, etc.),

- heavy rains,

- deep tilling,

- overcrowded or overgrazed areas, or

- soil erosion (e.g. wind, water, or wallows).

The spores brought to the surface can easily be ingested by cattle while grazing and cause infection.

Spores concentrate in low spots when floodwaters evaporate and infect cattle that drink standing water. During droughts, animals graze closer to the ground and may consume soil. Contaminated feed and soil excavation can also spread anthrax.

Clinical Signs of Anthrax in Beef Cattle

Anthrax in cattle has a very rapid onset. Once spores have been ingested, they infect macrophages (cells that are formed by the immune system in response to an infection), germinate and begin to multiply. The cells then produce a lethal toxin that kills body cells and causes excess fluid to accumulate in body tissues. Once the bacteria begin to multiply in the lymph nodes, the level of toxins in the body increase rapidly and cause tissue damage and organ failure. It is believed that the disease symptoms only last for 2-3 hours, so the most common symptom is sudden death. Very rarely observed symptoms are:

- trembling

- high temperature

- difficulty breathing

- convolutions and collapsing before death.

Often blood does not clot after death resulting in bloody discharge from any body openings (rectum, mouth, nostrils, etc.).

Diagnosis of Anthrax in Beef Cattle

Anthrax is a federally reportable disease and therefore your veterinarian must be notified if anthrax is suspected. Infected herds will not be quarantined or eradicated.

Anthrax is a federally reportable disease and a provincially notifiable disease in some provinces. Contact your veterinarian if you suspect anthrax on your farm. Veterinarians will collect blood samples to test for the anthrax bacteria. If anthrax is detected, it will be reported to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. The provincial agriculture department may also be notified. The CFIA no longer investigates, tests, quarantines, vaccinates, or assists with anthrax mortality disposal, but some provinces may pay for diagnostic anthrax tests and provide advice on proper disposal and control.

Do not cut the carcass open. If anthrax is responsible, you want to keep the carcass intact to prevent blood leakage and exposure to air (which promotes anthrax spore formation). If the carcass has already been opened the spleen will be swollen, and there will be blood and fluid in the body cavities.

For any animal that dies suddenly and unexpectedly, cover the carcass with a tarp and call your veterinarian immediately. This will help prevent scavenging and disease spread.

Treatment of Anthrax in Beef Cattle

Anthrax is susceptible to most antibiotics, so prompt treatment of animals at the earliest sign of illness should be effective. Treatment with antibiotics does counteract the vaccine though, so they should not be provided to animals that were recently vaccinated.

Prevention of Anthrax

The best way to prevent the disease is by preventing the production and dispersal of spores.

- In consultation with your veterinarian, vaccinate cattle against anthrax if the disease has been a historical or current concern in your area, or the area you purchase forages.

- Manage grass so that it is not over grazed, taking particular care during drought conditions

- Clean and disinfect any footwear or tools that may have come in contact with infected soils

- Wash clothes separately that were worn when dealing with sick animals

- Avoid using detergents that contain calcium as disinfectants (e.g. use bleaches that contain sodium hypochlorite, not calcium hypochlorite) when anthrax is suspected, as calcium preserves spores

Vaccination

An anthrax vaccine for beef cattle is licenced and available in Canada. After an initial vaccine and booster 2-3 weeks later, the vaccine provides immunity for approximately 1 year. Where acute risk of anthrax exists, vaccination is recommended three to four weeks before exposure.

Anthrax vaccination is most effective 3-4 weeks before exposure. Antibiotics can interfere with immunity if administered 8 days before or after vaccination.

Ask your veterinarian if vaccination is recommended in your herd. Vaccination is typically recommended if anthrax has historically occurred in an area, or in an area a producer purchases hay from. Producers can obtain the vaccine through their veterinarian, who can order it from a supplier.

While it is tempting to discontinue vaccination when cases have not occurred in the higher risk area for years, it is important to remember that spores can survive for decades and can easily resurface with changes in farming practices or weather patterns, so the risk is still present.

Although antibiotics such as penicillin can treat anthrax when used soon enough, it is important to not administer antibiotics within 8 days before or after vaccination, as they will interfere with immunity provided by the vaccine.

Disposal of Mortalities from Anthrax

Proper disposal of mortalities helps limit the spread and recurrence of anthrax. The recommended process for disposal of dead cattle that may have contracted anthrax is a 3-step process:

- Prevent blood or other fluids from leaving the carcass by plugging all body openings with an absorbent material (paper towel, cloth etc.), and covering the entire head with a heavy-duty plastic bag, that is secured by tape or tied securely.

- Protect the carcass until disposal by covering it with a tarp, or other heavy plastic and weighting down the ends to prevent animals from getting in. This step is important even if you will be disposing of the carcass quickly, as it prevents anything from opening the carcass and spreading spores while setting up for disposal.

- The recommended method of disposal is by incineration. Your veterinarian can tell you if incineration is legal in your area, recommend the best fuels to use, and the safest way to manage the incineration.When done properly, incineration completely destroys the bacteria and spores. Incineration should be done slowly so that all that remains is ashes and a few small pieces of bone. The ashes should then be soaked with an appropriate disinfectant (such as 10% formalin or 5% solution of lye (sodium hydroxide) and buried using deep burial best practices.

| If anthrax is suspected, |

|---|

| DO notify your veterinarian |

| DO remove surviving animals from the pasture |

| DO try to prevent scavenging |

| DO NOT move dead animals |

| DO NOT call for deadstock pick-up |

| DO follow the veterinarian’s instructions regarding deadstock disposal |

If incineration is not an option, deep burial is also an acceptable practice, but should only be used when incineration is not a viable option. With burial, spores will still be present and therefore carcasses should buried deep enough (6-8 feet) to prevent contaminated spores from being brought to the surface through weather or farming practices, yet 3 feet above the water table. Include the top layer of soil from where the animal was found dead as it is likely to be contaminated with spores. Do not bury carcasses in flood-prone areas.

If the carcass is not incinerated or buried, the anthrax bacteria will be exposed to air and form infectious spores as it decomposes. Deadstock pickup also increases the risk of future anthrax outbreaks by spreading the spores over a wider area.

It is important to consult with your municipality or county about any permits that are required for incineration or burial, and record the coordinates of any burial or burn location on your farm.

When disposing an infected carcass, be sure to cover any open wounds you may have as it is possible to contract the cutaneous form of the disease if a break in your skin is exposed to the bacteria. Wear closed toe footwear, pants, long sleeve shirts and gloves when handling contaminated animals to minimize the risk of disease transmission, then wash clothing separately. Disinfect boots and wash hands and arms thoroughly. Anthrax does not naturally disperse in the air, so a breathing mask isn’t necessary.

Previous research has also shown that calcium products such as lime protect spores rather than damage them. Read the label of any disinfectants used to ensure that they do not include lime or other calcium products.

Refer to the CFIA website for additional details on how to dispose of contaminated carcasses, and talk to your veterinarian or local ag specialist for advice.

Prevalence of Anthrax in Beef Cattle

Cases of anthrax sporadically occur across the prairie provinces. Approximately 20-25 outbreaks have occurred in Canada since 1967. The most significant outbreak occurred in Saskatchewan and Manitoba in 2006 where more than 800 animals died of the disease on more than 150 premises. Repeated outbreaks have also occurred in the Mackenzie Bison Range in the Northwest Territories and in Wood Buffalo National Park in Northern Alberta.

Anthrax prevalence depends on both weather patterns and geography. Anthrax spores require alkaline conditions to survive, so locations that naturally have alkaline soils are at a higher risk.

The ‘perfect storm’ for an anthrax outbreak is a heavy rain or flooding in the spring to bring spores to the surface, and then a drought later on which cause cattle to graze close to the ground and pick them up. Together these conditions increase anthrax prevalence but either a drought or a flood is enough to increase the presence of spores, and producers should take precautions during these weather patterns.

A study conducted in Saskatchewan after the 2006 outbreak found that farms in which outbreaks occurred had higher levels of flooding, wetter pastures, shorter pasture grass length, and higher density of animals in a pasture. It also found that the timing of vaccination after the first observed case in a rural municipality (in cattle herds that were not previously vaccinated) affected herd survival rate. As can be expected, the sooner that herds were vaccinated, the lower the death loss on farm.

Anthrax has occurred almost worldwide. Prior to the early 1960’s, 90% of anthrax in Canada was found in Ontario and Quebec. This is believed to have been due to contamination of fields by imported animals and materials for the textile industry. Since strict laws are now in place to control the washing and disinfecting of un-tanned hides and raw wool, it is more commonly found in western Canada.

Seasonal Prevalence

Anthrax is most common at 20°C or higher; cases in Western Canada since 1999 have mostly occurred from July through mid-September, and have followed periods of hot and dry or hot and wet weather.

Anthrax is rarely seen in the winter. When observed, the disease was due to feeding of contaminated feeds, such as stored forages that were cut too low to the ground in contaminated areas.

Danger of Anthrax to Humans

In rare cases, producers or veterinarians handling infected cattle may be infected through a cut or skin abrasion. Symptoms generally appear within 7 days of exposure. A raised itchy bump like an insect bite appears and develops into a painless ulcer (1-3 cm in diameter). A black spot appears in the center within 2 days, and adjacent lymph glands may swell. Immediately contact your doctor if this occurs. There is about 20% mortality if untreated; mortality is rare if treated with antibiotics. The disease is not known to spread from person to person.

- References

-

1. The Cattle Site. 2014. Anthrax. http://www.thecattlesite.com/diseaseinfo/197/anthrax/

2. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2013. Anthrax – Fact sheet. http://www.inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/anthrax/fact-sheet/eng/1375205846604/1375206913111

3. Epp T., Waldner C., Argue CK. 2010. Case-control study investigating an anthrax outbreak in Saskatchewan, Canada- summer 2006. Can Vet J. 51(9)973-8

4. Merk Manuals. 2012. Overview of Anthrax. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/generalized_conditions/anthrax/overview_of_anthrax.html

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at [email protected]

This content was last reviewed September 2024.