Improve Your Bottom Line with the Power of Feed Testing 🎙️

CLICK THE PLAY BUTTON TO LISTEN TO THIS POST:

Listen to more episodes on BeefResearch.ca, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music or Podbean.

Now that cattle feed is harvested or being harvested, it’s time to start thinking about testing that feed. While visual assessment can help separate the good quality feed from the poor-quality feed, it is not going to help you determine the energy and protein content – only a feed test can accurately provide this information.

For the most accurate results, it is best to test your feed shortly before cattle consume it or when management decisions are to be made, but you’ll need to leave adequate time for the results to come back so you can plan for supplemental feed if it’s needed.

For example, if you harvested your feed at the end of August and sent the sample off mid-September, then you should have your results back by the end of September at the latest, giving you between then and when you start winter feeding to source any supplemental feed you might need.

Why feed test?

- Develop appropriate rations that meet the nutritional needs of different classes of beef cattle and stages of production.

- Identify nutritional gaps that may require supplementation including trace minerals that are often deficient in cattle across Canada such as copper and selenium.

- Prevent or identify potentially devastating problems due to toxicity from mycotoxins, nitrates, sulfates or other minerals or nutrients.

- Avoid production problems, such as reduced conception or poor gain caused by mineral or nutrient deficiencies or excesses.

- Economize feeding and possibly make use of opportunities to include diverse ingredients such as fruit and vegetable waste.

- Accurately price feed for buying or selling.

Accurate knowledge of feed quality, particularly the operation’s forage base allows beef producers to develop feeding strategies for specific production scenarios and minimize the over- or under-feeding of nutrients. By so doing, one is able to achieve desired production targets and save on supplemental feed costs.

Read more on the BCRC’s Have You Had Your Feed Tested? post.

How to collect feed samples

Any feed type that will be used to feed beef cattle can and should be analyzed at a lab to ensure the nutritional needs of livestock are being met. This includes silage, baled forages and straw, by-products, baleage, grain, swath grazing, cover crops and corn.

The amount of sample to send to a lab will vary based on lab specification. Typically, a one-quart, zip-style plastic bag is enough sample. However, more may need to be sent depending on the number of tests requested.

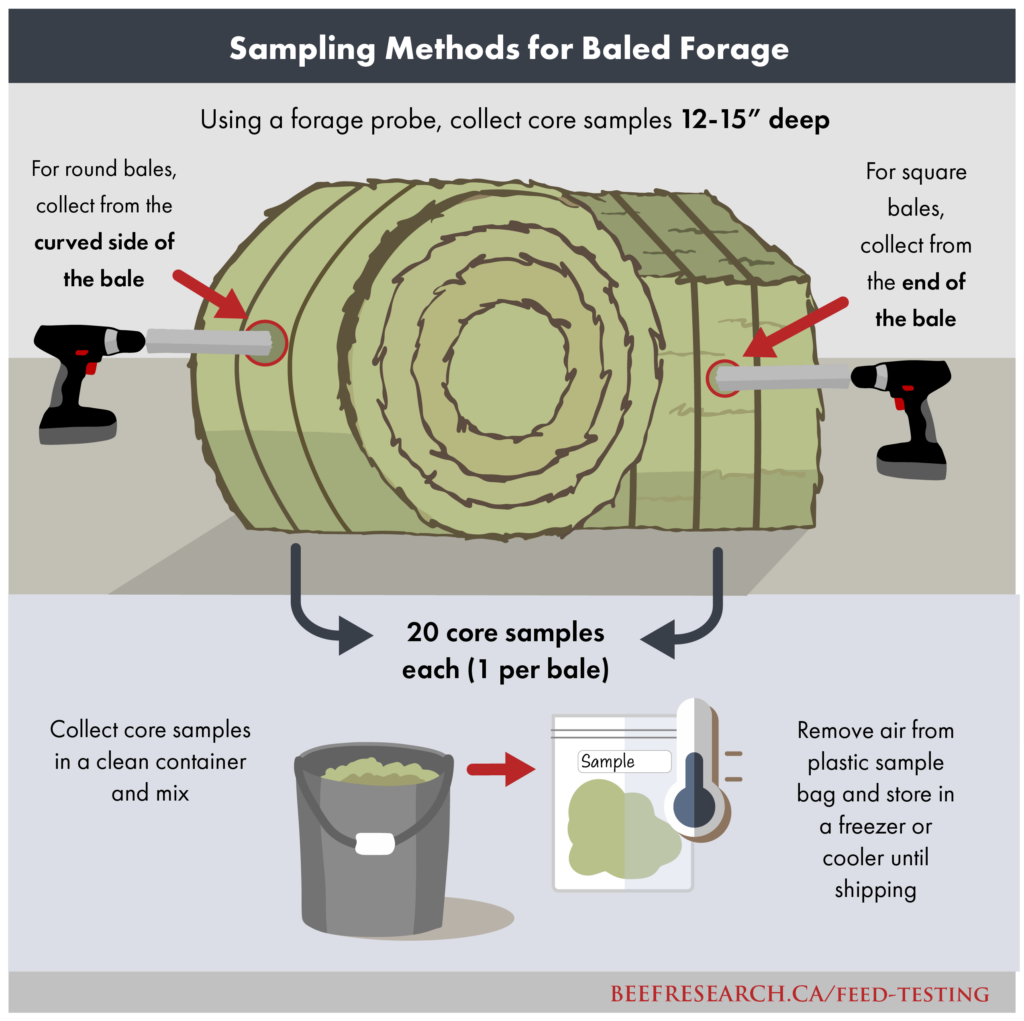

For baled forages, group the forage to be sampled into lots, which could be based on forage maturity, variety, harvest date, a single field or a single cutting.

Use a forage probe to acquire the minimum recommendation of 20 cores for each forage lot you wish to submit. Once you have the sample collected, put it in a plastic zip bag and clearly label it. Samples should be stored in a cool location, such as a refrigerator or cooler with ice packs, until shipping to the chosen lab.

For silage and high-moisture grains there are different recommendations for sampling depending on the type of storage system utilized:

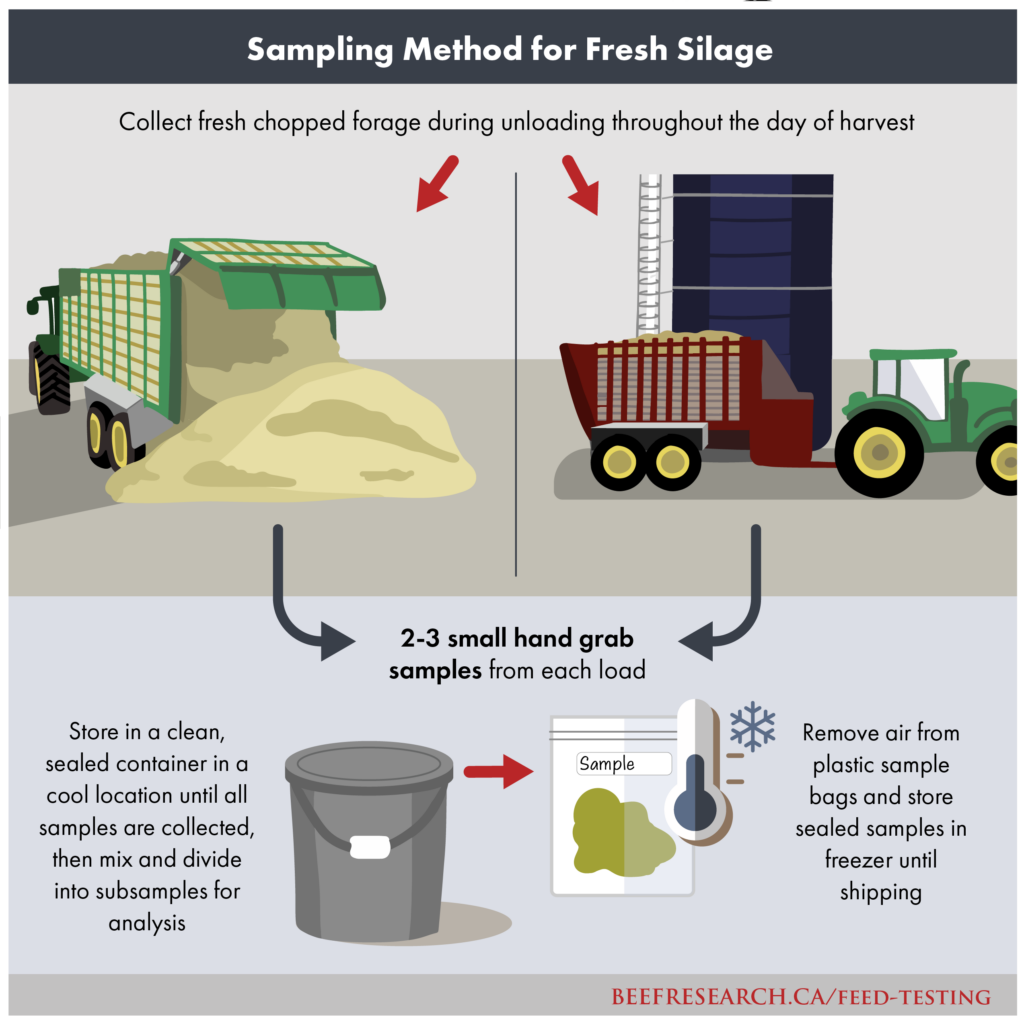

- Hand-grab samples can be collected for fresh silage from each load throughout the day of harvest. Sampling fresh forage gives you advanced knowledge of the nutritional quality of the stored forage. The fiber and protein fractions should not change significantly following harvest if proper ensiling and fermentation has occurred.

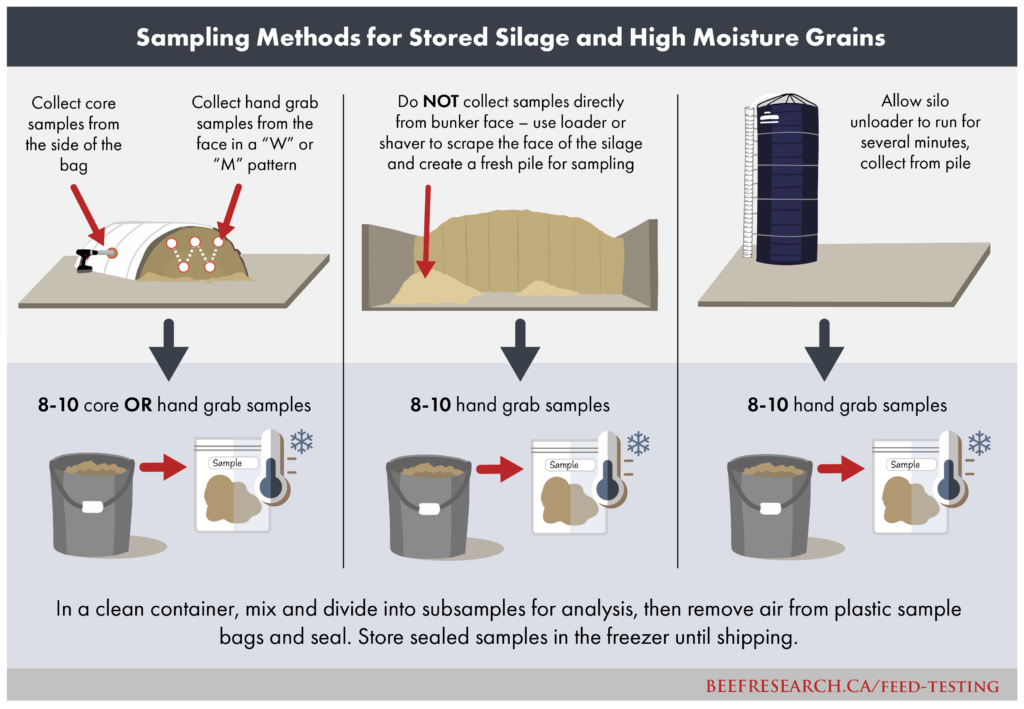

- If the silage is stored in a bunker or pit, the face should be scraped using a loader or shaver to create a fresh pile for sampling. Collecting hand-grab samples directly from the face is not recommended as this presents a safety hazard.

- Hand-grab samples can be collected across the face of silage stored in a bag following a W or M pattern. If collecting from the side of the bag using a forage probe, holes should be sealed afterwards to preserve forage quality.

- When stored in a upright silo, allow the silo unloader to run for several minutes prior to collecting a sample. The sample can be taken from a pile made by the silo unloader or out of a feed cart if loading directly into a feed cart. DO NOT sample from the two to three feet at the bottom or top of the silo.

- Mix samples in a clean container to create a composite sample and then subsample for analysis. Seal composite subsamples in a plastic sample bag, seal (removing as much air as possible), label and store in a freezer until shipping.

It is important to wait a minimum of four weeks after ensiling before sampling. This should be adequate time for the fermentation process to be stabilized.

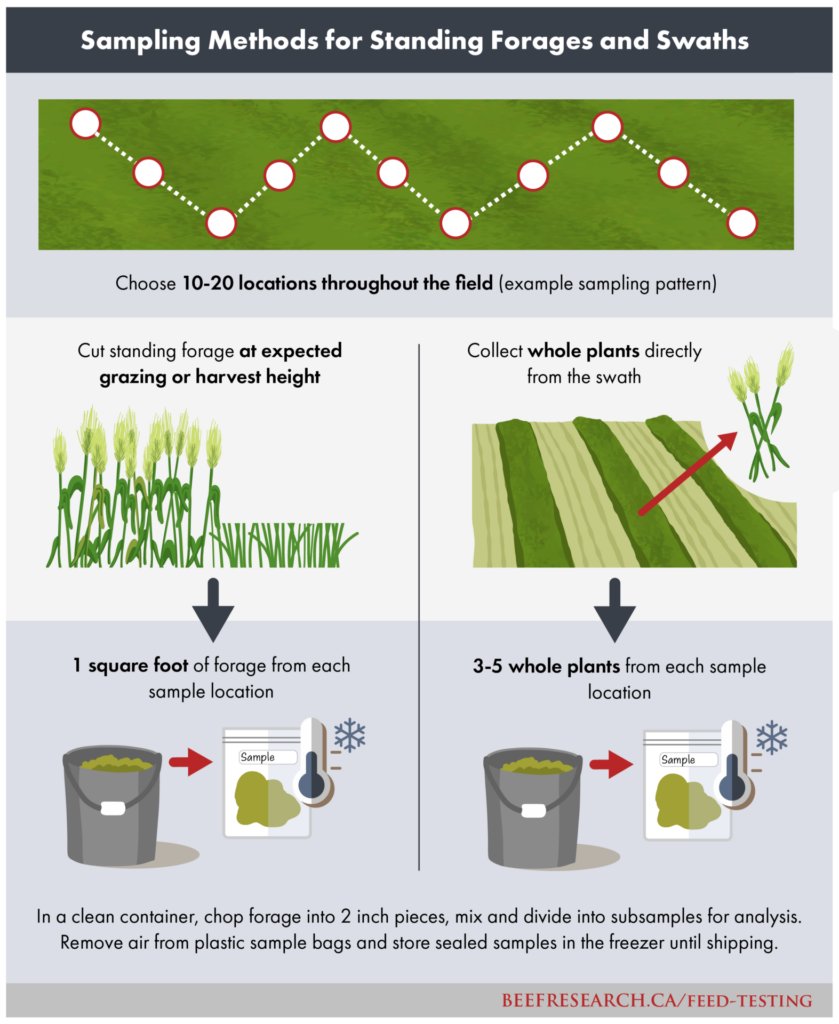

For swath grazing or standing forage, obtain representative samples of the sward (swaths) or the whole plant from 10 to 20 locations throughout the field.

Chop sampled forage into two-inch pieces, mix and divide into composited subsamples for analysis. Remove air from plastic sample bags and store in a freezer until shipping.

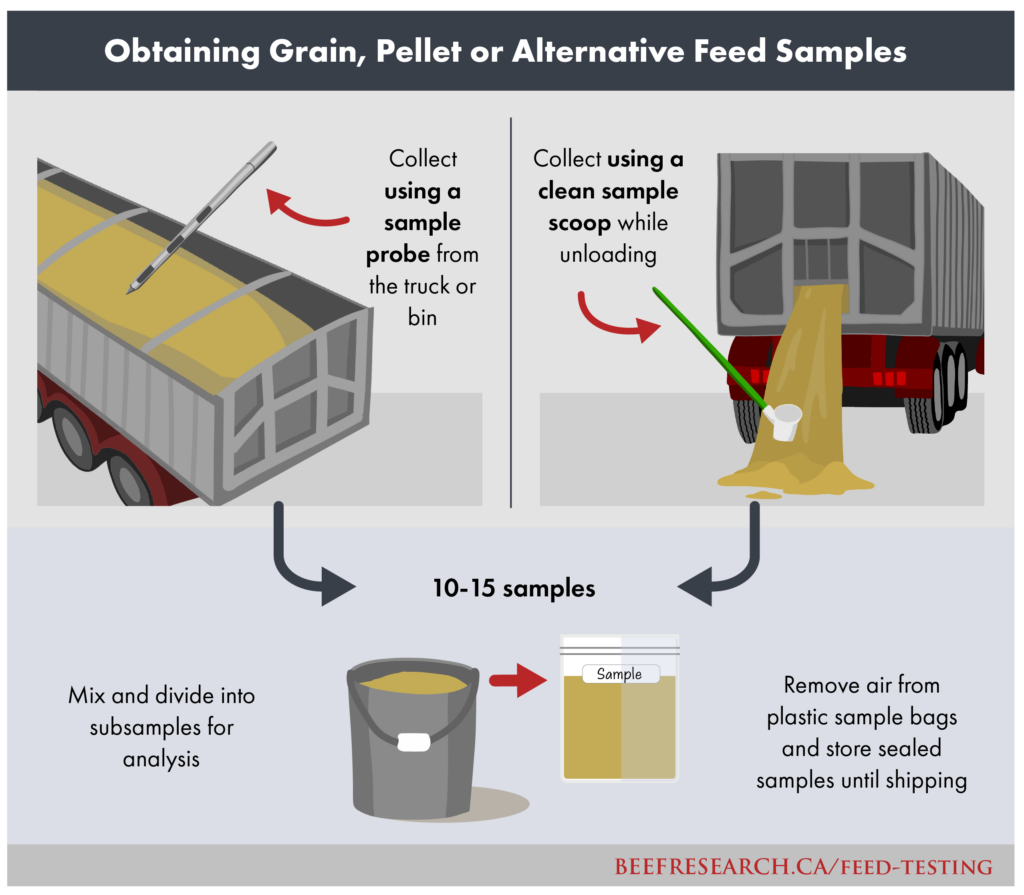

For grains, pellets or alternative feeds, 10 to 15 samples from each truckload or bin should be collected using a clean sample probe or scoop. Samples should be collected throughout the load representing a good cross-section of the truck or at regular frequency throughout the entire unloading process.

Interpreting lab results

Most labs provide basic information on protein, moisture content, energy, total digestible nutrients, fibre and some vitamins and minerals. More specialized tests may include results for nitrates, toxins, relative feed value (RFV) and other parameters. Consult our list of Canadian feed-testing laboratories.

The BCRC’s Tool for Evaluating Feed Test Results allows producers to see how a single feed meets the basic nutritional requirements of different classes of cattle in different stages of production under normal circumstances.

Laboratory results are often reported as both “Dry Matter” and “As-Fed” bases. Dry Matter (DM) refers to the moisture-free nutritional content of the sample. Always formulate rations on a DM basis.

Interested in feed testing? What’s next?

- Do you have the right tools, including a forage probe? Are the samples you’ve collected representative of your feed types?

- Assess your feed resources. What types of feeds are you planning to use, and which tests best suit your forage types? Do you want a standard feed analysis or a more specialized one?

- Evaluate your goals for feed testing. What is motivating you? How do you plan to use the results? Have you considered contacting a nutritionist, agrologist or veterinarian who can work with you to help interpret the analyses?

- Are there potential risk factors you want to avoid? For example, are you concerned about the risk of mycotoxins in barley or nitrates in a crop that was stressed? Have you or your neighbours had particular problems in the past?

- Understand the realities of potential results and study your feeding options. If your feed is poor quality or contains potentially dangerous toxins, how can you use it best? Do you have experience using poor-quality feed? Do you understand the risks of using potential problem feeds? Consider budgeting your quality feed for the higher production requirement periods.

Sharing or reprinting BCRC posts is welcome and encouraged. Please credit the Beef Cattle Research Council, provide the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you have chosen to share the article by emailing us at [email protected].

Your questions, comments and suggestions are welcome. Contact us directly or spark a public discussion by posting your thoughts below.