Genetic literacy is an important tool to achieving your beef cattle operation’s goals. However, understanding genetic terms and phrases can be challenging when they are used differently in various contexts. Visualizing a concept in a real-life setting can also be a hurdle when terms are not easily understood. This glossary is intended to serve as summary of genetic terms and phrases you may encounter with a brief description of the term and to provide an understanding of how the concept can apply on your operation.

Click on the first letter of the term you are searching to jump to that section:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A

Animal ID: This allows you to identify and track individual animals. Genetically, this is an important record to keep as it allows you to track the history of that animal (i.e. parentage and beyond) as well as associate performance and treatment records to a specific animal to make more informed breeding and management decisions. Animal ID is typically done two ways, with a farm ID in the form of an ear or brisket tag and a CCIA RFID tag (which can be linked to the farm ID in your personal records).

Average daily gain (ADG): Also referred to as growth rate, average daily gain is the average amount of weight an animal gains each day. It is calculated by taking the amount of weight gained (lbs or kg) and dividing that by the number of days that weight gain was accumulated. As a record, ADG can be important to monitor for benchmarking and goal-setting purposes to ensure your cattle are on target for goal weaning, breeding or finishing weights.

B

Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluation (BBSE): A standardized assessment of a bull’s likelihood of accomplishing pregnancy during a defined breeding season.

Bull selection: Bull selection is one of the most economically important decisions made on a cattle operation. This refers to choosing a bull that will help to achieve your operation’s goals, whether that be more efficient calves or purebred bulls to sell to commercial clients, there are specific traits each producer is looking for in a new bull.

Breed complementarity: Using two breeds in your breeding program where the genetics of one breed complements the other breed. Example: using a bull breed to pass on growth and desirable carcass traits to breed to crossbred cows which would result in an ideal calf for the feedlot on a cow that has the mothering ability and milk output to raise the rapidly growing offspring.

Breeding objective: The genetic plan for your breeding program that considers management, marketing and environmental factors to meet your breeding goals.

C

Calf ID: Calf ID is a means of identifying the progeny of your breeding females. This is typically done with ear tags that will allow you to easily identify who their dam (and sometime sire) is along with a personal ID number for farm-level identification. In addition to the calf ID, producers should keep identifying information regarding the calf that can help in the management of than animal (i.e. treatment records, coat colour, sex, calving ease).

Calf performance: Keeping records on the performance of your calves and being able to compare from year to year is a great indicator of genetic progress, tracking your goals and even identifying gaps to set new ones. Calf performance can be measured in numerous ways including, weaning weight, average daily gain, health, vigour, carcass qualities, etc.

Calving ease: This is a trait that can be selected for in bulls. Calving ease is expressed as the probability of a calf being born unassisted or the probability of a heifer having an unassisted calving.

Calving index: This is the average calving interval of all cows (or a group of cows) in a herd at any given time, expressed in days. Knowing this number can allow you to benchmark within your herd and understand which cows are below, above or right on average, which can help to inform culling and replacement decisions.

Calving interval: This is the time (in days) between one calving and the next for the same cow. For beef cattle, the goal is a calving interval of 365 days or less. This record can help producers set goals for their reproductive program rather than a monitoring parameter.

Carcass traits: These are traits that will directly impact the suitability and potential improvements of that animal as beef on the rail. This includes marbling, back fat, rib eye size, tenderness, etc.

Cash cost: Out-of-pocket expenses that are paid in cash and are dependent on production practices and quantities and prices of required inputs (e.g., seed, feed, fertilizer, pesticides, custom services, vet expenses) throughout the production year. Producers might want to know their profit after cash costs are accounted for to estimate available cash at the end of the production period. Some cash costs vary depending on production, land area and number of head, and others may be fixed like insurance, licensing and taxes.

Conformation and conformation issues: Proper conformation is a key element when selecting replacement bulls and heifers. These are desirable and undesirable skeletal and muscular structures of an animal, meaning how they are built and how they carry themselves. This includes proper hoof structure, pastern angle, hind and front leg structure and hip structure, in addition to teat and udder shape and proportionality. Basic conformation (i.e., having good legs and feet) are indicators that that animal can remain sound in the herd for longer. Any sort of indication of bad conformation should be culled from the herd to avoid retaining those genetics and impacting the longevity of breeding animals in your herd. Animals with correct conformation are better able to survive in a pasture-based system and perform the functions needed to be bred, calve and raise that calf.

Cow performance: Keeping records on cow performance to compare from year to year is important to track genetic progress as well as tracking and identifying goals for your operation. Cow performance can include calving interval, body condition scoring, calving ease, temperament, foot and udder scores as well as the quality of calf (e.g., percentage of body weight weaned) she has raised. Understanding individual cow performance allows identification of top and bottom performers which allows producers to make informed breeding and culling decisions to streamline the achievement of goals.

Crossbreeding: Breeding cattle of different breeds together to capture the production benefits from breed complementarity and hybrid vigour.

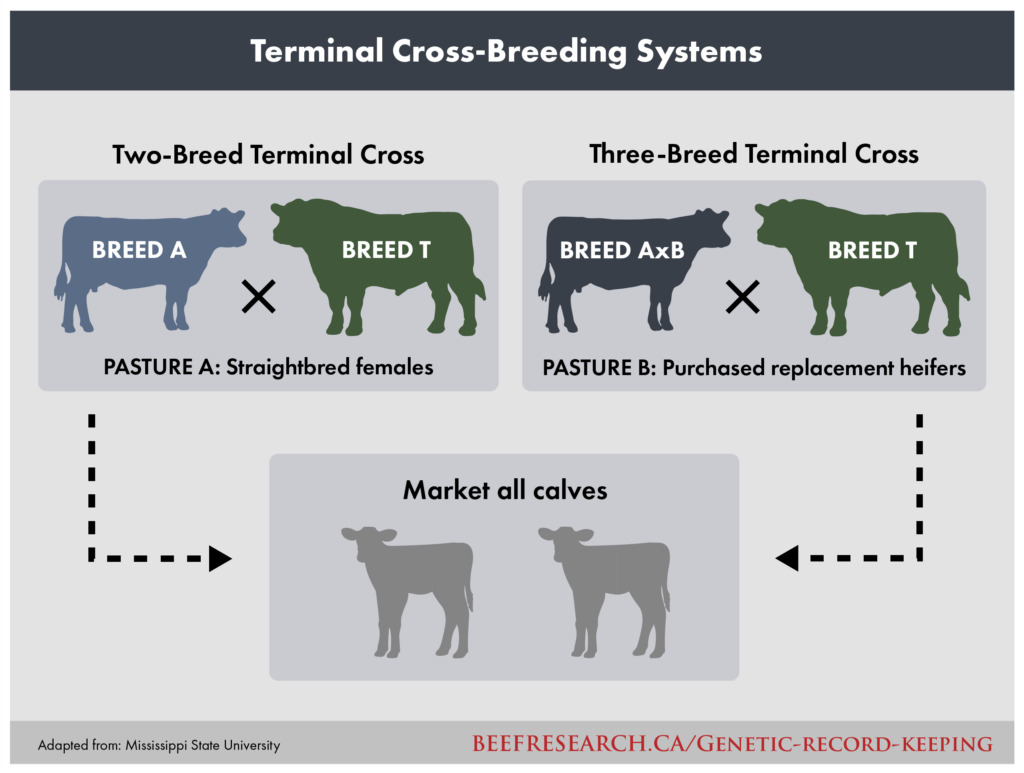

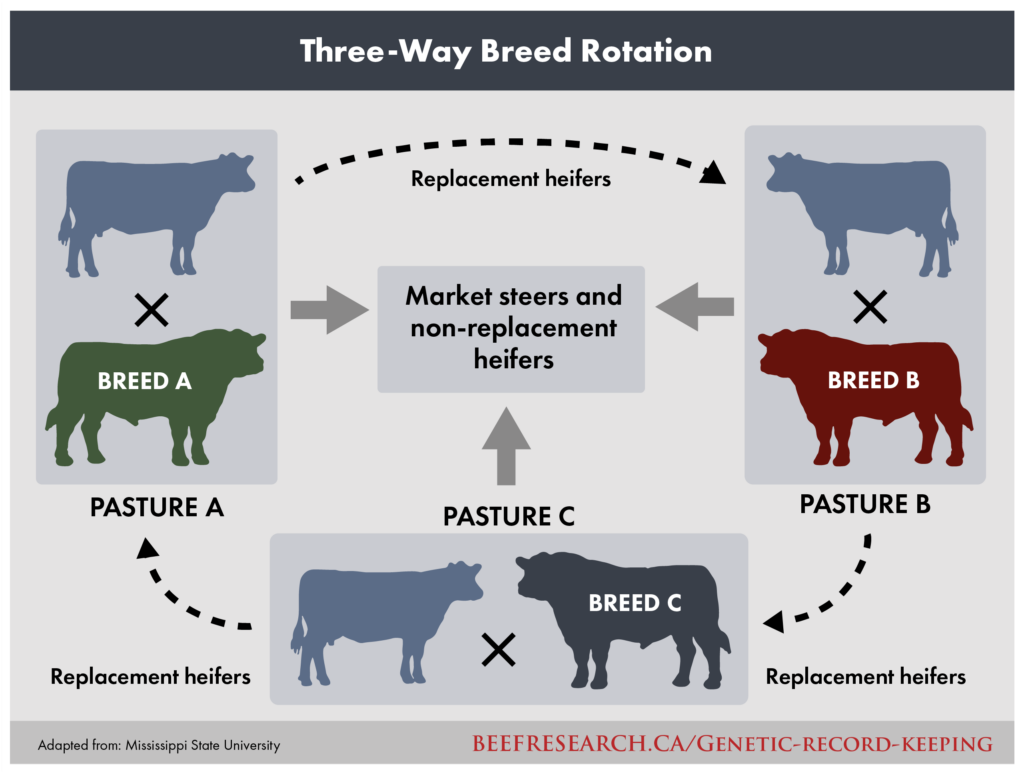

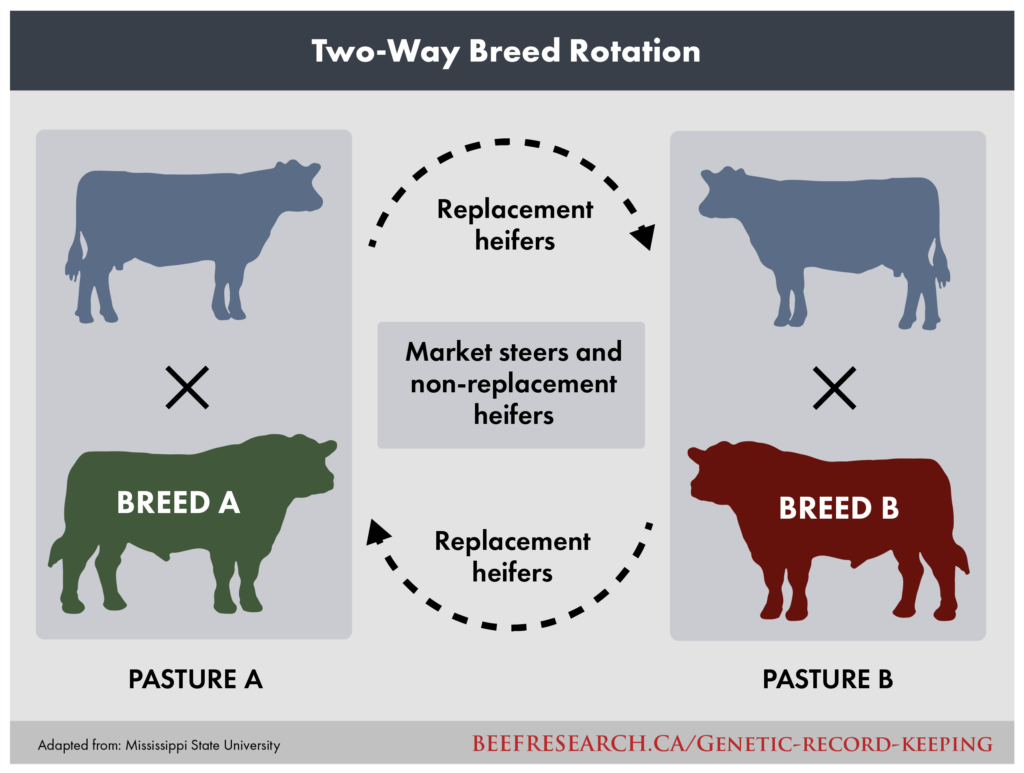

See Terminal Crossing, Two-Way Rotation and Three-Way Rotation for specific crossbreeding examples.

Culling traits: These are traits that will help determine objectively which animals should be culled from the breeding herd. Having a clear definition and boundary for what will be kept and what will be culled based on genetics and performance allows desirable traits in your herd to be exaggerated by removing what is undesirable.

D

Dry Matter Intake (DMI): Measure of the amount of feed a cow consumes per day on a moisture-free basis.

Dystocia: This is a term to describe an abnormal, slow or difficult calving at any stage of labour. There is a direct negative impact on calves when this occurs (e.g., hypoxia, acidosis, vigour, stillborn) as well as the cow (e.g., trauma, nerve damage causing weakness or paralysis, inflammation of the uterus, prolapses). It is important to record dystocia events as a record in order to indicate when there is a significant increase in dystocia (e.g., new herd bull causing calving issues, nutritional deficiencies or nutrition changes resulting in larger calves) or if there is reoccurring dystocia in a particular cow which may warrant culling or an indication to sell her heifer calves rather than retaining for replacements risking more common dystocia incidences on the farm in the future.

E

Economically relevant traits (ERTs): Traits that are directly associated with a source of revenue or cost.

Efficiency traits: Sometimes confused with growth traits, efficiency traits are used to predict which animals will gain more weight (or the same amount of weight faster) while eating less (or the same amount) of feed as other animals. Typically, efficiency traits are highly heritable, such as dry matter intake (DMI), feed efficiency/feed to gain ratio (F:G) and residual feed intake (RFI).

Expected progeny differences (EPDs): Estimates the genetic potential of that animal as a parent. At their core, EPDs are the difference between the predicted average performance of an animal’s future progeny and the average performance of the progeny of another animal for specific traits. EPDs can allow you to strategically select bulls for the traits that will aid in achieving your operation’s goals.

f

F1 females or bulls: F1 stands for “first cross” which is the offspring resulting from mating a purebred sire to a purebred dam of another breed resulting in an F1 offspring that is 50% breed A and 50% breed B. Breeding an F1 female or bull will produce an F2 offspring, and crossing that F2 animal will result in an F3 offspring, and so on.

G

Growth traits: Traits that are affiliated with increased growth like birth weight and average daily gain (ADG).

H

Health treatment records: These records keep track of treatments and any sort of medically related procedures or tests. When taking these records, the identity of the animal should accompany dates, details, type of treatment, dose, route, frequency and duration of treatment should be kept. These records help to inform antimicrobial stewardship and can also be an indicator of an outbreak if the number of treatments has increased when compared to past years.

Heritability: is a value between 0 and 1 and measures the genetic influence of a particular trait, without consideration for environmental factors. Reproductive traits tend to have low heritability rates (i.e., low likelihood of passing down the trait genetically, more influenced by environment or management), while growth and carcass traits have higher heritability rates (i.e., higher likelihood of passing down the trait genetically and can select for).

Hybrid vigour (Heterosis): An increase in performance seen when crossing two genetically different individuals. Seen as individual heterosis (i.e., increase in production seen in the crossbred offspring, generally an improvement in growth) and maternal heterosis (i.e., increase in calving percent, higher weaning weight, longevity and reproductive traits in crossbred dams compared to straightbred dams).

I

Inbreeding: Mating of parents that have very similar genetics or relatives in common. When inbreeding occurs, the calf is more likely to have two sets of identical genes which can increase the likelihood of expressing recessive genes that negatively impact production.

Inbreeding depression: Reduction in performance due to mating of highly related individuals. It most negatively impacts reproductive traits.

Indicator trait: A trait that adds accuracy to the prediction of an economically relevant trait (ERT). These traits have no explicit economic benefit other than its correlation to an ERT.

M

Maternal traits: These are traits selected for calves that have the potential to enter the reproductive herd as replacement animals (heifers or bulls). Maternal traits include calving ease, milk production and traits related to female fertility. Depending on your operation’s size, goals, preference and breed will determine whether a producer will select a bull with terminal or maternal traits.

O

Opportunity cost: Any option for extra profit or cost savings a producer may be giving up in pursuit of their current production practice or marketing strategy.

Example #1 – the potential added calf weight when using a bull with a higher EPD for growth and efficiency traits than the current herd bull.

Example #2 – the potential cost savings from only keeping replacements from good-mothering cows that do not need assistance while calving.

Example #3 – the increased profit from keeping records to strategically inform breeding replacements and culling decisions using historical records and farm-specific data.

P

Parentage testing: Parentage testing confirms the identity of the sire of the offspring by comparing the calf’s DNA to potential bulls. Typically, these tests are used to confirm the accuracy of pedigrees and paternity information, accurately identifying the sire so that the calf’s performance is accurately associated with the right sire and the EPDs can be updated appropriately. These tests not only confirm pedigree but also can provide information to make important management decisions in a commercial cow-calf operation setting. A typical parentage panel consists of 120 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Post-weaning weights: These weights measure the growth of an individual animal after weaning, indicating the ability of that calf to perform on its own without influence from the dam. These records are important as weaning weight is largely influenced by the dam and the quantity and quality of milk and care she is providing to that calf. However, once weaned, it becomes apparent if that calf can adjust to new feed and environments to hit targeted growth rates. This information can provide useful information when making breeding decisions to ensure you have a calf that can perform well on pasture in addition to in a backgrounding or finishing setting.

Pregnancy status: Pregnancy checking in late summer or fall (depending on your breeding season) provides you with information to make the best economical decisions for your herd. Having an accurate number for open heifer and open cow rates that can be compared from year to year can help identify a wreck before it happens. A significant increase in open rates can indicate nutritional or management issues that should be addressed. Beyond this, knowing which cows or heifers are open and which are not allows you to make an informed open cow/heifer marketing strategy. Open cow and heifer prices at the time of preg checking will help indicate whether it is more economical to keep those females and sell them in the spring or sell them right away. Information is power, and knowing what your operation’s “normal” is and what is actively going on in your herd can help boost that bottom line.

Purebred: Purebred cattle are comprised on only one beef breed, like straightbred, but they also can come from a sire and dam that are registered with that specific breed association and where all ancestors (or most) are registered.

R

Reproduction traits: Reproduction traits typically have low heritability and include fertility, age at first calving, calving interval and scrotal circumference.

Residual Feed Intake (RFI): A measure of feed efficiency. Describes the difference between an animal’s actual feed intake and expected requirements for growth and maintenance.

S

Selection indexes: Combine several traits into one value. Differences in two animal indices is the expected average value differences of their calves.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP): Substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. This is the most common form of genetic variation between individuals.

Straightbred: The breeding herd is comprised of only one breed of cattle, resulting in a homogenous herd where cattle responses to environmental and nutritional factors are easier to predict.

T

Temperament: Often overlooked, temperament is a very heritable trait that can have major implications on the day-to-day operation of your farm. While the main reason producers select for temperament is safety, there is also evidence to show that calmer cattle have improved performance and beef quality. While handling practices and training can improve the fear and stress experienced by individual cattle associated with human handling, some cattle are just genetically more docile than others and will raise calves that are more likely to be docile. The same goes for cows genetically predisposed to be more agitated and aggressive who will raise calves who will likely express those same behaviours.

Terminal crossing: Breeding a terminal bull (i.e., a bull with high genetic merit for growth, efficiency and carcass traits) to a dam that will be marketed after weaning. Can use a two-way or three-way rotational system to achieve these crosses.

Can use a two-way cross, breeding a breed A dam to a breed B bull where replacement heifers are bought in and all calves are marketed. This takes advantage of individual heterosis in the offspring.

Can also use a three-way terminal cross where crossbred (breed A x breed B) replacement heifers are bought in and bred to a breed C sire. All resulting calves are marketed. This allows an operation that still relies on buying replacements every cycle to still take advantage of individual and maternal heterosis.

Terminal traits: These are selected traits to yield calves that will not enter the reproductive herd. Bulls selected for terminal traits will have offspring that are superior when it comes to growth, efficiency and carcass quality.

Three-way rotation: Similar to the two-way rotation with another breed added. Females sired by breed A are bred to breed B, females sired by breed B are bred to breed C, and females sired by breed C will be bred to breed A. Market steers and keep heifers for replacement. There is more individual and maternal heterosis potential compared to the two-way rotation but requires three breeding pastures and more labour due to the increased complexity of the system.

Trade-offs: This occurs when selection for a desirable trait results in reduced performance in a different desirable trait (e.g., high YW = high MCW).

Two-way rotation: Method of crossbreeding that uses two different breeds of sire to take advantage of individual and maternal heterosis. Females sired by breed A will be bred to breed B and females sired by breed B are bred to breed A. Heifers will be retained as replacements and bred to the breed they were not sired by, while steers are marketed.

W

Weaning weight: This is a very heritable trait defined as the weight of a calf at the time they are being weaned from their dams. This is typically the weight they will be marketed at should they be sold to a backgrounding or finishing operation at that time, and it is an indicator of growth efficiency from birth. Weaning weight is typically adjusted to a common age of 205 days to ensure accuracy to compare across individuals or when analyzing an average.

Y

Yearling Weight: This is the combined pre-weaning and post-weaning weights of a calf. Yearling weights are typically adjusted to a common age of 365 days to ensure accuracy to compare across individuals or when analyzing an average.