A bull is a significant investment to the herd and requires proper management to ensure effective performance and longevity. Bulls play a critical role in achieving the breeding goals for the herd in order to achieve long-term environmental and economic sustainability. Bulls account for 50% of the herd’s genetics and will influence the current calf crop and the future breeding herd for generations.

On This Page:

| Key Points |

|---|

| Under- and over-conditioned bulls can have reduced performance which may lead to lower conception rates. |

| It is recommended that bulls have a post-breeding recovery period of at least four to eight months. |

| The physical ability of a bull to breed can be evaluated using a standardized Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluation (BBSE) provided by a veterinarian. This exam is also an opportunity to identify any indicators of disease or injury that may limit a bull’s ability to perform. |

| Frequent observation of bulls during the breeding season is important to detect any lameness, lack of libido or inability to mount or successfully breed that might be caused by injuries to the bull’s legs, back or penis. |

| Unvaccinated bulls also run the risk of transmitting disease to the cow herd which, in turn, can result in reduced conception rates and increased abortion rates. |

| Ideally, bulls will have a body condition score (BCS) of 3-3.5 at the time they are on pasture with females. |

| Be sure bulls are coming from a known and reputable source with a detailed history, especially when it comes to vaccination and health treatments. |

| Animals infected with trichomoniasis, vibrio or leptospirosis should be culled for slaughter. |

| Considering the costs of natural service and lost genetic opportunities, artificial insemination may be a profitable breeding option, for both commercial and purebred cattle herds. |

| Consistent record-keeping helps identify areas of weakness and strength of the herd and can guide genetic advancements desired within the herd. Whether the goal is improved growth and performance at the feedlot or maternal traits of importance, selecting a bull that can aid in achieving that goal while working within a budget is critical. |

| Bull value is dependent on: – Individual performance – Environment (pasture productivity) – Management (bull-to-cow ratio) – Markets (calf price) |

Breeding Management

Year-round management is required to ensure bulls perform during the breeding season. Bulls serve two primary purposes: to enhance reproductive traits of the breeding herd and to transmit long-term desirable herd genetics through their offspring. Body Condition Score (BCS) is a good indicator of bull health. Under- and over-conditioned bulls can have reduced performance which may lead to lower conception rates. Ensuring bulls are as healthy as possible going into breeding season and are given the necessary time to recover post-breeding is important to maximize bull longevity.

There are three phases of bull management:

- Pre-breeding or conditioning (two months)

- Breeding season (two to three months)

- Post-breeding (seven to eight months)

An effective bull-to-cow ratio is anywhere between 1:20 and 1:30 with younger bulls being closer to 1:20. A common rule of thumb is a bull is able to breed as many females as it’s age in months (i.e., an 18-month old bull can handle 18 females). However, there is disagreement regarding these recommendations as there have been instances of lower ratios, more cows per bull, being effective1. Observing bulls over one to two years of breeding should give breeding managers an idea of the mating capacity of their bulls and inform breeding plans accordingly.

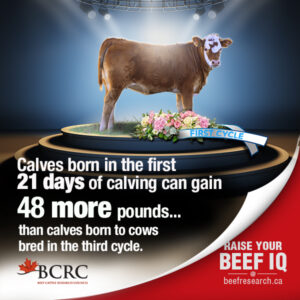

The industry recommendation for calving season length is 63 days (or three cycles). This is often rounded down to 60 days for cows and 42 days (or two cycles) for heifers. This means putting bulls out for 60 or 42 days in total to achieve a tight calving season, uniform calf crop and ensure there is enough time for bulls and cows to recover fully prior to the next breeding. Managing the breeding period within a specific time frame also shines light on the value of breeding management beyond pregnancy rates. While a high pregnancy rate is desired, there are potential economic losses if at least 60% of cows aren’t calving in the first 21 days (i.e., first cycle).

Other benefits of a shortened calving season include:

- More calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season allowing producers to market larger, more uniform groups of calves and increase their profit potential

- Increased cow longevity

- Heifers born earlier have potential for greater pregnancy rates, remain in the herd longer and produce one more calf in their lifetime compared to those that are calved later in the season

- Easier to time herd vaccinations

- Easier to compare calves because of increased uniformity

Given the level of exertion required during the breeding season, it is recommended that bulls have four to eight months to recover between breeding seasons2.

The BCRC’s Value of Calving Distribution Calculator allows producers to see their current calving distribution and the short-term economic benefit of moving to the industry target of 60-25-10-5. This target is where 60% of females calve in the first cycle, followed by 25% calving between 21-42 days, 10% between 42-63 days and the remaining 5% calving in the fourth and final cycle. This condenses breeding, and calving, into a season of three cycles.

Changes to breeding management before, during and following the breeding season can result in substantial changes to pregnancy rates. Producers should not rule out issues such as appropriate bull-to-cow ratios for the bull age, pasture size, terrain type or sexually transmitted disease if a drop in pregnancy rates is observed. Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluations (BBSE) pre-breeding can give valuable insight into if bulls are prepared to handle the upcoming breeding season and identify preventable issues before it is too late.

Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluations

Turning out a bull that is infertile or unable to physically breed regardless of the cause is a huge liability to cow-calf producers. The physical breeding ability of a bull can be evaluated using a bull breeding soundness evaluation (BBSE) provided by a veterinarian. This exam is also an opportunity to identify any indicators of disease that may limit a bull’s ability to perform.

There are four components of a BBSE:

- Scrotal exam (circumference (cm), resilience and tone of the testicles, evidence of frostbite or other injuries, and inspection of the epididymides attached to the bottom of the testicle)

- Physical exam to identify any injuries, abnormalities or disease that could impair breeding

- Semen quality (sperm count, motility and % abnormalities)

- Libido – the bull’s desire and drive to breed. This can be done by observing bull behaviour before and during the early part of the breeding season. This can be difficult to evaluate, even in a research setting.

There is good evidence 3 from field studies in western Canada that suggest a positive correlation between scrotal circumference and pregnancy rates, however, there is an upper limit. Increasing scrotal circumference is correlated with an increase in seminal quality up to 38 cm, with no further observed differences in bulls with larger testes.

Dr. Roy Lewis discusses the importance of a BBSE and how to use that information to make valuable breeding decisions in this BCRC webinar, Setting Bulls Up for Success – The Importance of a Bull Soundness Evaluation:

The results of a bull breeding soundness evaluation can change from year to year. Some bulls who fail could be retested in a couple of weeks depending on the circumstances of the failed BBSE. The veterinarian performing the BBSE should be able to inform whether a bull is worth retesting or if the problem is likely permanent. Having annual BBSEs as part of the herd health management protocol provides assurance that there have been no changes in semen quality or breeding potential from one year to the next in bulls that might otherwise appear normal. Without a BBSE, disease, trauma or frostbite can cause significant negative implications to breeding, which could go unnoticed until there are severe consequences. Completing a BSE prior to turn-out and keeping an eye on bulls during the breeding season to make sure they are still in good physical health can improve fertility on cow-calf operations.

While there are no formal recommendations for the timing between a BBSE and turn-out, enough time should be allowed to replace animals that fail the BBSE but not so early that bulls will be impacted by frostbite or other health challenges before the start of breeding season.

Reducing the Risk of Poor Fertility

Bulls should be monitored for excessive weight loss and illness. Heat detection, breeding attempts and semen quality can be reduced in bulls that are under-conditioned or sick. Lameness due to foot rot or injury can be an important cause of poor pregnancy rates on pasture as bulls are less likely to seek out cows in heat.

Bulls are sometimes overlooked when it comes to regular vaccinations. Clostridial vaccines as well as vaccinating against bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus, bovine respiratory disease (BRD) and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) are also important for protection of valuable breeding stock.

Producers should also be aware of potential venereal (sexually transmitted) diseases that could reduce fertility of the breeding herd. A sharp drop in pregnancy rate with no other plausible explanation could be a result of venereal disease and warrants veterinary consultation.

Frequent observation of bulls during the breeding season is important to detect any lameness, lack of libido, or inability to mount or successfully breed that might be caused by injuries to the bull’s legs, back or penis. This is particularly vital in single bull breeding pastures. Injured bulls, if detected, can be replaced before too much time is lost during the breeding season.

Vaccinating Bulls

Producers can consult with a veterinarian to determine what vaccination protocol is best suited for that particular breeding herd and environment. While most producers say they vaccinate to prevent wrecks before they happen, a western Canadian survey showed, while almost all producers (97%) vaccinated their cows with at least one product, only 72% reported vaccinating bulls4. However, bulls are just as in need of protection from potentially devastating diseases as the rest of the herd.

Bulls should follow the same herd health program/schedule as the cow herd. It is critical that bulls be vaccinated against clostridial diseases (e.g., Blackleg), bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus and other bovine respiratory viruses. BVD infection can lead to poor conception rates, and both BVD and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) can cause abortions in cattle. Exposure to these diseases is common in unvaccinated herds.

Veterinarians recommend vaccinating bulls three to four weeks prior to breeding to allow for the immune system to build protection. Bulls that are unvaccinated risk succumbing to disease causing reduced performance and potentially death. Unvaccinated bulls also run the risk of transmitting the disease to the cow herd which in turn, can result in reduced conception rates and increased abortion rates. Vaccinating the cow herd only is not enough to achieve herd immunity. If BVD is suspected in the herd, testing and culling persistently infected carrier animals can be considered as an additional management tool.

The Cost-Benefit of BVD Vaccinations and the Cost-Benefit of BRD Vaccinations allows producers to input their own herd data to see the potential savings from vaccinating cattle for those diseases that negatively impact fertility. There is evidence to suggest that these vaccines are effective. For BVD, an average decrease of 85% has been reported for fetal infection and a 45% decrease in abortions5. The IBR vaccine has been reported to reduce the risk of abortion by 60% on average6. Field studies in Western Canada have shown a significant improvement in pregnancy rates and decrease in abortion rates for vaccinated compared to unvaccinated cows on community pastures7,8. Overall, a 5% increase in pregnancy rates is typically seen in vaccinated versus unvaccinated herds5.

BVD and IBR was the most common type of vaccination reported in mature cows and bulls in a recent survey that was part of the Western Canadian Cow-Calf Surveillance Network. Bull vaccination presents an important opportunity to decrease the risk of reproductive failure. For example, the testicular tissue of bulls can potentially remain infected with BVD for prolonged periods and provide a source of the virus to susceptible cows and heifers9.

Every time producers are putting bulls through the chute, they should ask if the bulls are due to be vaccinated and proceed accordingly. Discussion with veterinarians can also be beneficial to identify any additional specific vaccines that could be added to the vaccination protocol depending on geographic location, animal health history (abortions) and risk of exposure to cattle from other herds.

LAMENESS IN BULLS

Lameness can be an important cause of poor pregnancy rates on pasture as increased body temperatures due to infection, stress and pain means bulls are less likely to seek out cows that are in heat and can also temporarily reduce sperm production. There are many potential causes of lameness stemming from genetics, environment, nutrition, injury, infection or a combination of these factors.

Foot rot is the most common cause of lameness on Canadian operations. A commercial vaccine is available for foot rot and a recent survey found 40% of producers use it on their bulls4, though the effectiveness of the vaccine is variable. Veterinarians can provide insight to determine if vaccinating against foot rot is right for a particular herd.

Accurate diagnosis is important for the successful treatment and prevention of lameness. Consistent monitoring and quick treatment are key to reduce the long-term impacts lameness can have on the herd. To avoid unnecessary administration of antibiotics, producers should not assume all lame cattle have foot rot – an accurate diagnosis requires close inspection.

bULL NUTRITION

Maintaining the condition of bulls is essential to maximize breeding performance. Bulls should be monitored for excessive weight loss and illness. Heat detection, breeding attempts and semen quality can be reduced in bulls that are under-conditioned or sick. Alternatively, over-conditioned bulls will have more fat deposits in the neck and scrotum which can impair temperature regulation (most importantly cooling) of the testes.

Spermatogenesis (sperm production) in the bull is reliant on the temperature of the testes being maintained a few degrees lower than body temperature. Impaired cooling mechanisms can result in a reduced amount of oxygen available to the testes which can ultimately reduce testosterone, resulting in reduced sperm production and an increase of sperm abnormalities. High energy diets have also been linked to reduced sperm production, storage, motility and increased sperm abnormalities compared to bulls fed medium energy diets.

Ensuring bulls have a balanced diet in the off-season including salt and minerals is essential to get them prepared for the upcoming breeding season. This is especially important for mature bulls who can lose condition quickly. Both under- and over-conditioned bulls can have reduced performance which may lead to lower conception rates. Feed testing is the best way to ensure proper nutrition is being met.

Evaluating the Body Condition Score (BCS) of bulls is an effective way to ensure that bulls are in good condition going into the breeding season. Ideally, bulls will have a BCS of 3-3.5 (scale of 1 to 5) at the time they are on pasture with females. Bulls can lose between 100 and 200 lbs during the breeding season so it is important to make sure they are in good health and condition prior to turn out. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that as a bull’s back fat thickness increases past a BCS of 3.5, fertility decreases emphasizing the need to ensure bulls are in proper condition at the beginning of the breeding season.

BULL HOUSING

Shelter during the winter months can have significant implications on a bull’s ability to breed in the upcoming season. Adequate bedding is essential to avoid testicular frostbite which can negatively impact fertility.

After breeding season, instead of introducing a new bull to an already established group of bulls, it may reduce fighting for social dominance to introduce all of the bulls to new surroundings at the same time. Alternatively, putting younger bulls in with older bulls instead of matching age groups can also reduce fighting (similarly aged/sized bulls tend to fight with each other more than bulls with larger age or size differences, though younger bulls may still challenge older bulls if they seem “weaker”).

Providing more space can reduce fighting as well. If possible, let bulls establish their social pecking order prior to breeding turnout. When mixing and co-mingling bulls, it is important to observe how they are settling in. Monitor bulls closely for the first few days when comingling to observe and intervene in case of excessive fighting to avoid bulls becoming injured or causing significant damage.

Across Canada, bulls used for natural service are exposed to variable environments during the breeding season. Depending on the space, terrain and the age/body condition of the bull, time spent with females, the bull-to-cow ratio and other breeding management factors may need to be adjusted.

BIOSECURITY

Biosecurity is important in bull management within the herd and when bringing in new animals. It is a producer’s first line of defense in preventing disease outbreaks by reducing the risk of new diseases entering the herd and minimizing the spread of existing disease within the herd. Taking the necessary precautions when purchasing bulls, turning bulls out to the breeding females and ensuring equipment is appropriately cleaned/disinfected can help reduce the incidence of disease and prevent reproductive disruptions.

Following are biosecurity considerations when integrating new bulls into the established herd:

- Be sure bulls are coming from a known and reputable source with a detailed history especially when it comes to vaccination and health treatments.

- Keep new bulls in a separate pen for at least two weeks for observation. During that time, you will be able to see if there are any obvious health concerns that should be addressed prior to turning them out with the other bulls or cows.

- Vaccinate bulls three to four weeks prior to turning them out with females.

- Avoid sharing bulls with neighbouring herds or community pastures.

- Buy virgin bulls to ensure new bulls are not carrying venereal diseases that may spread to the rest of the herd.

Prior to turn out, bulls should be vaccinated and show no signs of poor health. If there are any concerns with the health status of a bull, he should be removed and treated as soon as possible and, if possible, replaced with another sire.

Sharing bulls with neighbouring herds or communal pastures can create a biosecurity concern. It is valuable to discuss the herd health risks with a veterinarian and consider taking additional precautions in these scenarios. This includes vaccinating the breeding herd for common and reproductive diseases, testing external bulls for trichomoniasis, ensuring proper parasite control, having a mitigation plan for diseases like Johne’s Disease and quarantining cows and bulls after they have returned from a community pasture.

Producers should also be aware of the potential risks posed by unplanned mixing with other herds when developing bull testing and vaccination programs for venereal and other reproductive diseases. Maintaining fences and removal of animals “visiting” from other herds as quickly as possible is important in protecting herd health, but ensuring a herd is completely closed to outside exposure can be very difficult.

vENEREAL (SEXUALLY tRANSMITTED) DISEASE

Most beef herds in Canada continue to use bulls to breed their females, and therefore, are susceptible to venereal (sexually transmitted) diseases. The most common venereal diseases of cattle include trichomoniasis (trich), vibrio and leptospirosis (lepto). Although these diseases occur infrequently, the results of infection can be devastating causing abortions, infertility and in some cases, death.

CAUSES

- Trich is caused by a protozoan parasite called Tritrichomonas foetus (T. foetus).

- Vibrio is caused by bacteria called Campylobacter fetus subsp. venerealis.

- Lepto is caused by pathogenic bacteria of Leptospira spp.

Trich and vibrio are transmitted through physical contact when a bull breeds a cow. Once a cow is infected, they act as a source of infection for other non-infected bulls within the herd which then spread the disease(s) to other cows. Cows that are in that breeding pasture but become pregnant and calve successfully are unlikely to carry the infection. If a bull tests positive for either disease, they will most likely remain infected for life.

Lepto is typically contracted from direct contact between animals or indirectly from contact with infected urine or the products from abortion. Wild animals often serve as a source of infection for cattle through direct contact or contaminated water sources. Bacteria that cause lepto can survive in surface water, stagnant ponds, streams or soil for weeks, even months.

Cows who contract the disease are a risk to non-infected cattle and have potential to spread/contract the disease to/from other species including pigs, horses, dogs, rodents, wildlife and humans10. Strains that are not specifically adapted to cattle (incidental strains) are likely to cause outbreaks within the herd while strains specifically associated with Bovine Leptospirosis (e.g., from serogroup Hardjo) can colonize the reproductive system of bulls and cows and result in embryo losses and delayed conception.

SYMPTOMS OF VENEREAL DISEASE

Low pregnancy rates in bull-bred beef herds can be caused by venereal diseases.

None of these diseases cause clinical signs in the bull. The semen of affected bulls will also appear normal on a Bull Breeding Soundness Examination. However, venereal disease outbreaks can result in up to 50% dry rate11 though some case studies suggest there is potential to be much higher. However, note that some strains of leptospirosis will result in sick animals with a variety of clinical signs within the herd.

CONSEQUENCES

Herds infected with trich or vibrio will typically have:

- Low or very low pregnancy rates due to early embryonic death

- High numbers of open cows at calving in herds that do not pregnancy test

- Early abortions

- Extended breeding season, with cows that conceive much later than expected (i.e., cows can lose their first pregnancy and rebreed later in the breeding season – particularly in herds that do not have a defined breeding season)

Newly infected cows may still conceive, but their resulting pregnancy is commonly lost between 40 and 70 days after breeding. Cows that have aborted will typically start to cycle again but experience temporary infertility for one to five months as they clear the infection.

Herds infected with lepto will typically have:

- Low pregnancy rates

- High number of open cows

- Infertility

- Weak calves

- Reduced body condition

- Abortions at any stage of gestation

- High fever

- Kidney failure

- In rare cases, death

DIAGNOSIS

Preventative testing can be done at the same time as the BBSE by a veterinarian prior to bull turn-out. Testing bulls for venereal disease is required by most community or multi-patron pastures to reduce the risk of disease transmission. These tests can help avoid an outbreak before it happens. However, testing can be done at anytime and should be considered if an outbreak is suspected and to ensure the problem doesn’t repeat in following years.

Testing for Trich

Producers should test and cull infected bulls for slaughter, not resell to another producer.

For bulls that are available for testing, a scrape sample should be collected from the inner surface of the sheath known as the prepuce (preputial scraping). For trich, the scrape sample is flushed into a pouch with a culture broth to grow the parasite. This test is performed by a vet and can be done during a BBSE.

Herds with suspected or confirmed trichomoniasis should test their bulls three times at weekly intervals at a minimum, with either culture or PCR before considering them negative. For routine screening of larger bull batteries with low risk of disease, using PCR on pooled samples made from up to five individual bulls has been found to identify a positive bull greater than 90% of the time12. This is comparable to the detection rate of a single culture or PCR test on an individual bull.

Testing for Vibrio

Testing for vibrio usually involves the collection and culture of a scrape sample from the prepuce of a bull. However, the bacteria causing vibrio are very temperature sensitive and commonly die en route to the diagnostic laboratory if transported for over 24 hours. PCR tests for vibrio have been developed and evaluated to be 85% accurate at identifying positive and negative bulls when sampled in the field. While not perfect, it is an improvement over what has traditionally been available to practicing veterinarians. This test is currently recommended for use when investigating poor reproductive performance, rather than screening low risk bulls, and is best utilized when other causes have been ruled out.

Testing for Lepto

The PCR analysis of urine samples are the most common way individual animals are diagnosed with lepto whether it be an incidental or adapted strain of lepto. The most accurate way to test for lepto is through bacterial culture. Unfortunately, this method is costly and highly technical. Lepto infection can also result in the development of a detectable number of antibodies and can be detected in the blood using a microagglutination test (MAT). Vaccines for lepto can also result in detectable serum antibodies. Antibody titre >800 are suggestive of a recent infection. However, some animals can shed the bacteria without having these detectable titres.

Other Tests

If the bulls are unavailable for testing, a diagnosis of trich, vibrio, or lepto can be determined from aborted fetuses or even the vaginal mucous of carrier females. However, finding an aborted fetus with trich or vibrio is uncommon and the short duration of infection in females can make finding infections difficult. Collecting samples for testing from females with obvious reproductive tract infections (pyometra) is most likely to provide useful information.

PREVENTION AND CONTAINMENT

Cows and bulls should be vaccinated for vibrio before going to communal grazing pastures for breeding.

Animals infected with trich, vibrio, or lepto should be culled for slaughter. Identifying and replacing positive bulls with virgin bulls remains the cornerstone of controlling both venereal diseases. If a venereal disease outbreak is suspected, cows that are open or which conceived late in the breeding season should also be removed from the herd especially if a bull has been proven to be positive. Cows that have their calf at foot are generally considered to be safe from spreading the disease further.

Vaccinations for vibrio are available and should be given to cows and bulls before going to communal grazing pastures for breeding, and in privately owned pastures where there is a risk of infection from within the herd or from a neighbouring herd. A vaccine for trich is available in the US but not in Canada. The evidence suggests that it provides some protection against fetal loss but does not effectively prevent infection. A lepto vaccine is available and is recommended in high risk areas as it is the cheapest way to control the spread. Cows and bulls in high risk areas should be vaccinated twice a year as it will prevent abortion, reproductive problems and usually stops the shedding of bacteria in the urine.

For herds at risk, veterinarians recommend using a multi-faceted approach to prevent a lepto outbreak. Vaccinations are recommended as well as management practices including controlling rats, fencing off potentially contaminated water sources, preventing the intermingling of species and treating infected animals with antibiotics. Although, efficacy of the control measures will be dependent on the strain of the infection.

Initiating a timed artificial insemination program is a method to prevent venereal disease, but still requires either heat detection or a bull for “clean up” and more labour.

Artificial Insemination

Although artificial insemination (AI) of cattle has been possible for 60 years, this technology has not been used widely in Canada’s commercial beef herd. Genetic evaluation of beef bulls has improved considerably in recent years, making bull selection more objective and reliable. Sexed semen, expected progeny differences (EPDs) and the ability to select for specific traits identified through DNA markers (genomic selection) are also now available, increasing the usefulness of AI to producers without sacrificing pregnancy rates. Considering the costs of natural service and lost genetic opportunities, AI can be profitable, even in commercial cattle herds.

A common criticism of AI in beef cattle is that not all females will be become pregnant, so clean-up bulls are always necessary. This is not entirely true; resynchronization protocols have been developed leading to management schemes exclusively for fixed-time AI, eliminating the need for clean-up bulls. In one study in Brazil, a cumulative pregnancy rate of 87.4% was achieved after three fixed-time inseminations in a 64-day breeding season. As an alternative, it is possible to greatly reduce the number of bulls needed, especially in large herds13. For example, with 100 heifers and a 60% pregnancy rate to fixed-time AI, only 1 or 2 bulls is required to clean-up as opposed to at least four without synchronization and AI. Another criticism is that all calves will be born on the same day. This is not true; synchronized cattle normally calve over a period of 2 to 3 weeks.

Cost of Natural Service

The true costs of natural sire service are often underestimated. Factors including annual maintenance costs, interest and bull performance should all be considered. For example, a bull that is expected to wean 21 calves weighing 550 lbs on average per year would be accountable for an estimated $1,394 per year. The annual maintenance cost for the bull, including winter feed costs, vet bills, yardage and pasture, is $850 per year. The salvage value of the bull is $2,375 and, over its lifetime, the cost of maintaining the bull for six years is $7,549.71.

If the bull successfully sires 144 calves over the six years, the break-even value, or the price you should be willing to spend on the bull, is $4,824.71, which results in a cost of $52.43 per calf. Since not all of the females will wean a calf, and many bulls may be lost or culled before six seasons of use, the real costs can easily exceed $60 per pregnancy.

Economics of AI

Depending on the protocol employed, it is estimated that fixed-timed AI is likely to cost $20 to $30 per female. Semen costs are in addition to this with typical prices ranging from $10-$30 per insemination dose.

Calculation of the true cost of a synchronization program must include the costs of:

- consumables,

- hired labor (e.g., inseminator),

- additional time required for management,

- semen costs and

- a charge for animal handling (including weight loss and use of facilities).

On the revenue side of the balance sheet, consideration should be given to:

- the length of the calving season,

- its effects on the provision of monitoring and assistance during calving and

- its effects on the uniformity of weaning weights (based on both sire and day of birth).

Semen Tanks for AI

Appropriate AI sire selection can result in substantial reductions in dystocia (calving problems) in heifers, and consequently, less interventions, more calves weaned and improved postpartum (after calving) reproductive performance.

Similarly, selection of sires with superior weaning weights, yearling weights, feedlot performance and carcass characteristics can improve the profitability of a cow-calf operation. These advantages will be of greatest benefit to the cow-calf producer that either retains ownership of the cattle or that is able to convince buyers to provide compensation commensurate with the cattle’s genetic potential.

With pasture breeding, it is difficult for a bull to sire more than 40 calves in a six- to eight-week calving period. Through fixed-time AI, the number of females that can be bred to a single sire in a day is virtually limitless. High-quality, highly sought-after genetics may be purchased through a semen supplier enabling astute producers to produce a more consistent group of cattle than ever before. As an alternative, a single bull of very high genetic merit can be purchased and used through fresh, extended semen in a fixed-time AI protocol, siring virtually limitless numbers of offspring.

Bull Management for AI

Fertility in an AI program is a product of female fertility, semen fertility, inseminator skill and timing of AI. It is vitally important to realize that a deficiency in any one of these components, or sub-optimal performance in two or more of these components, will substantially decrease pregnancy rates.

Semen should be examined before use or purchased from a reputable source and properly handled (including storage and thawing). If there is any question regarding semen viability, the semen should be examined prior to use.

Good management practices are necessary year-round, in addition to just prior to the breeding season. Good planning and communication, including written protocols and frequent consultations with a veterinarian, are essential. One should take into account resources, capabilities, intentions and breeding objectives in order to choose the most appropriate protocol.

Bull sELECTION

Bull selection is an important decision for cow-calf producers that has implications for both short- and long-term profitability. Which bull a producer selects will depend on operational goals, budget and preferred traits. Prior to purchasing a bull, it’s important to identify long-term herd goals to best select a bull that can assist in the desired outcomes.

Consistent record-keeping helps to identify areas of weakness and strength for the herd and can guide the type of genetic advancements desired within the herd. Whether the goal is improved growth and performance of the subsequent calf crops or improved maternal traits such as improved fertility and longevity for replacement females, bull selection is a critical component in achieving breeding goals while working within a preferred budget.

EPDs

Expected progeny differences (EPDs) are a prediction of the genetic potential that is expected to be passed on to the offspring from a parent. The accuracy of an EPD, or the prediction, increases as the performance data of more offspring are tracked. The accuracy of the prediction of an animal’s genetic potential can also be increased through DNA tests or genotyping, especially in younger animals who have yet to have data captured from offspring.

There are several EPDs available to evaluate a bull’s traits but interpreting them while considering trait selection interaction can be difficult. Most breed associations and other organizations have developed selection indexes which focus on economically relevant traits for specific operational goals (e.g., mature cow size, cow longevity, growth, carcass value, weaning weight, feed efficiency etc.) to assist and somewhat simplify the selection decision process. However, it is important to keep in mind the level of heritability of traits and therefore those traits that can be influenced through genetic selection and which are influenced through changing management practices.

Table 1: The impact of genetics or management changes on culling decisions

| Heritable/ Non-heritable | Range of heritability (%) | Improved primarily through genetics or management? | |

| Cow traits | |||

| Medium heritability | 28-32 | Genetics | |

| Milking ability | Medium heritability | 30 | Both |

| Foot conformation | Medium heritability | 21 | Genetics |

| Foot problems (rot, sand cracks, heel wart) | Not heritable | – | Management |

| Cancer eye | Heritable | * | Genetics |

| Temperament | Low to medium heritability | 10-30 | Both |

| Fertility traits | |||

| Calving interval | Low heritability | 10 | Management |

| Maternal ability | Medium heritability | 40 | Genetics |

| Vaginal Prolapse | Heritable | * | |

| Calf performance | |||

| Birth weight | Medium heritability | 32-47 | Both |

| 24-30 | Both | ||

| Feedlot gain | Medium heritability | 34-45 | Both |

| Pasture gain | Medium heritability | 30 | Both |

| Feed efficiency | Medium heritability | 40-45 | Both |

| Carcass traits | High heritability | 50 | Both |

Sources: The Beef Cow Calf Manual. Alberta Agriculture and Food (2008) and Guidelines For Uniform Beef Improvement Programs. Beef Improvement Federation (2010).

* These traits are known to be heritable, but a formal heritability study has not been conducted since the incidence is low and it would take thousands of animals to derive accurate heritabilities.

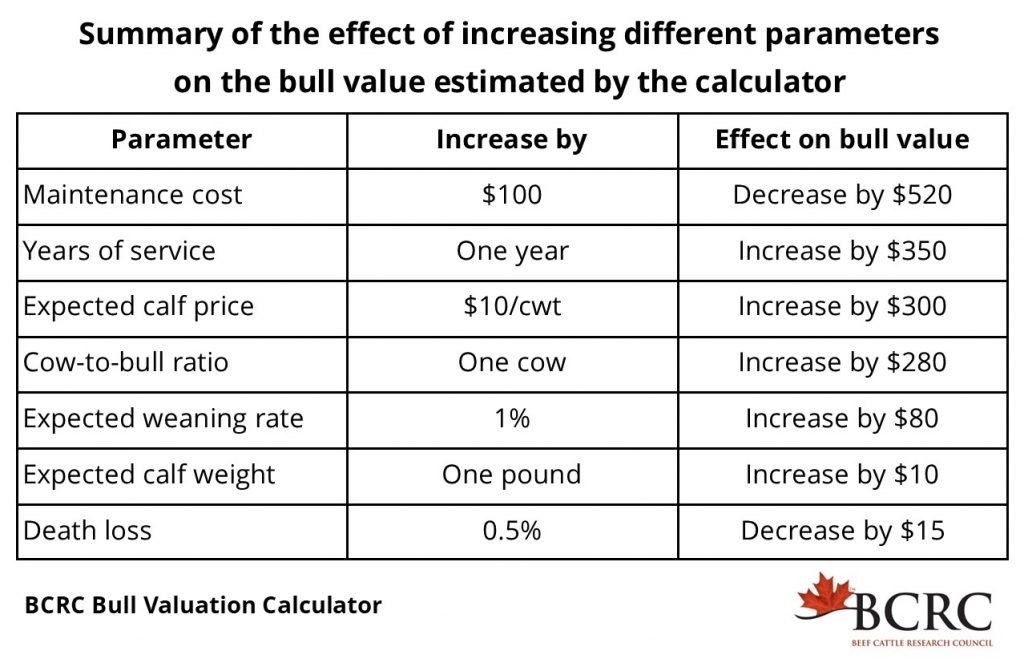

Bull Valuation

Identifying a fair price during sire selection contributes to increased efficiency and operation economics. Spending top dollar does not always achieve desired breeding goals or maximize financial return to the herd. Different traits will impact the operation’s bottom line differently depending on operational goals. It is important to evaluate how much an individual bull is worth to an individual farm or ranch and identify a price to pay that will allow a significant return on the investment.

Bull value is dependent on:

- Individual performance

- Environment (pasture productivity)

- Management (bull-to-cow ratio)

- Markets (calf price)

For example, large-framed bulls may have higher maintenance costs, but that may be offset by heavier calves at sale time.

Bull Valuation Calculator

The BCRC’s Bull Valuation Calculator is a tool available to beef producers to estimate a break-even bull price using personalized on-farm numbers.

Factors that significantly impact bull price include:

- Years of service

- Bull-to-cow ratio

- Expected price of feeders

- Bull maintenance cost

The value determined by the calculator is only an estimate and may not reflect the true break-even price. However, this tool can be used as a guideline, demonstrating how changing variables can affect the cost and value of a herd sire.

Bulls are significant investments in terms of up-front capital and the impact they will have on the future of the herd. Therefore, it is important to protect your investment through management to ensure bulls reach their full productive potential and maximizing longevity through biosecurity, nutrition and maintenance.

- REFERENCES

-

- 1. Day, M. (1999). Mating capacity of bulls; bull to cow ratio. Ohio State University.

- 2. Clarke, R. (2021). Managing bulls after breeding season. The Beef Magazine by Canadian Cattlemen.

- 3. Waldner, C.L., Kennedy, R.I., Palmer, C.W. (2010). A description of the findings from bull breeding soundness evaluations and their association with pregnancy outcomes in a study of western Canadian beef herds. Therio. 74(5), 871-883.

- 4. Waldner, C.L., Parker, S., Campbell, J.R. (2019). Vaccine usage in western Canadian cow-calf herds. Can Vet J. 60(4), 414–422.

- 5. Newcomer, B.W., Chamorro, M.F., Walz, P.H. (2017). Vaccination of cattle against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Micro. 206, 78-83.

- 6. Newcomer, B.W., Walz, P.H., Givens, M.D., Wilson, A.E. (2015). Efficacy of bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccination to prevent reproductive disease: a meta-analysis. Therio. 83(3), 360-365.

- 7. Waldner, C.L., Garcia Guerra, A. (2013). Cow attributes, herd management, and reproductive history events associated with the risk of nonpregnancy in cow-calf herds in Western Canada. Therio. 79(7), 1083-94.

- 8. Waldner, C.L. (2014). Cow attributes, herd management, and reproductive history events associated with abortion in cow-calf herds from Western Canada. Therio. 81(6), 840-848.

- 9. Voges, H., Horner, G.W., Rowe, S., Wellenberg, G.J. (1998). Persistent bovine pestivirus infection localized in the testes of an immune-competent non-viraemic bull. Vet Microbiol. 61(3), 165-175.

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Leptospirosis Infection.

- 11. Michi, A.N., Favetto, P.H., Kastelic, J., Cobo, E.R. (2016). A review of sexually transmitted bovine trichomoniasis and campylobacteriosis affecting cattle reproductive health. Therio. 85(5), 781-791.

- 12. Kennedy, J.A., Pearl, D., Tomky, L., Carman, J. (2008) Pooled polymerase chain reaction to detect tritrichomonasfoetus in beef bulls. J Vet Diagn Invest. 20(1), 97-99.

- 13. Baruselli, P.S., Ferreira, R.M., Colli, M.H.A., Elliff, F.M., Sá Filho, M.F., Vieira, L., Gonzales de Freitas, B. (2017). Timed artificial insemination: current challenges and recent advances in reproductive efficiency in beef and dairy herds in Brazil. Anim Reprod. 14(3), 558-571.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca.

This content was last reviewed January 2025.