Remarque : cette page web n’est actuellement disponible qu’en anglais.

Sur Cette Page:

On This Page:

Johne’s disease (pronounced “Yo-knees”), also known as paratuberculosis, is a long-standing infection that causes a very gradual thickening of the intestines reducing nutrients absorption and resulting in weight loss, diarrhea and eventually death. Johne’s disease primarily affects cattle and other ruminants, but has also been reported in pigs. The economic cost of Johne’s disease can be significant due to reduced weaning weights, later rebreeding, and losing or culling cows before they have recouped their production costs. Diagnostic tests are inaccurate (particularly in the early stages of the disease, and there are no effective vaccine and no effective treatments. Johne’s disease is very difficult to eradicate once it has become established in a herd, so biosecurity precautions are essential to prevent it from entering the herd through infected colostrum or breeding stock.

| Key Points |

|---|

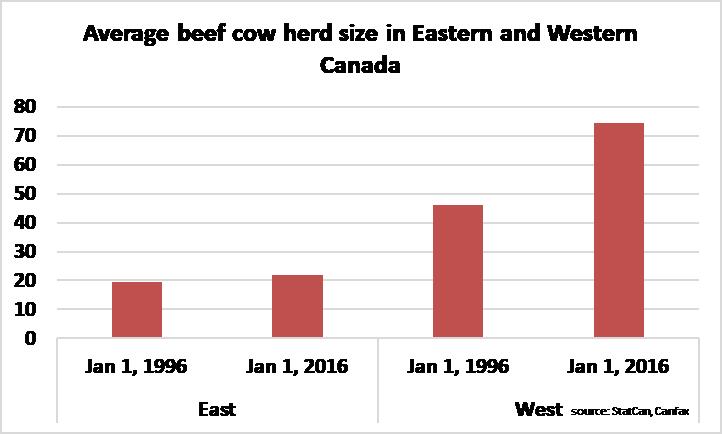

| There is concern that the risk of Johne’s disease in beef herds is increasing in part because of rapidly increasing herd sizes and herd dispersals |

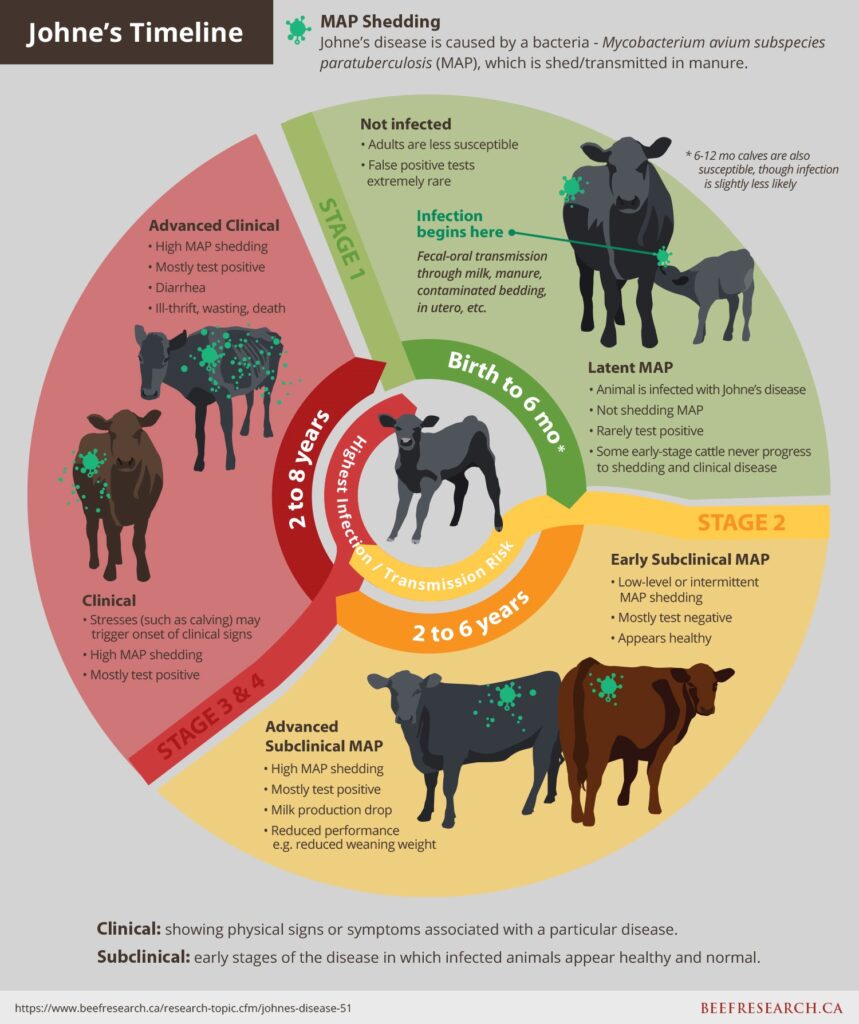

| Calves typically pick up the infection very early in life through exposure to colostrum, milk or manure from a Johne’s infected cow, but signs of the disease don’t become apparent until years later |

| Researchers estimate that from Johne’s Disease infects 1 to 2% of mature Western Canadian beef cows (5% of herds) and 2 to 9% of Canadian dairy cows (and 70% of dairy herds) |

| Cows with Johne’s disease have been shown to wean calves that weigh 50 pounds less than normal herd mates. |

| Clinical signs commonly occur between the ages of 2-6 and may include periodic to persistent diarrhea and progressive weight loss, both of which are non-responsive to treatment. |

| Diagnostic tests are unreliable for detection of pre-clinical infection in individual animals, there is no vaccine available in Canada, and there are no effective drugs for treatment of Johne’s Disease. Prevention is key. |

| The worst mistake a producer can make is to separate a Johne’s infected cow and keep her in the calving area in hopes that she will gain weight before being sold. |

Introduction

Johne’s disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). Calves typically pick up the infection very early in life through exposure to colostrum, milk or manure from a Johne’s infected cow, but signs of the disease don’t become apparent until years later. In the meantime, MAP typically harbors and multiplies in the small intestine. MAP can also be spread to areas outside the intestine, such as the uterus, lymph nodes, udder, reproductive organs of bulls, and may be excreted directly in milk or semen.

Several therapies have been investigated, but unfortunately no treatment has been found to be effective and economical for Johne’s disease. This is partly because there is an extremely long dormant period between infection and clinical disease. Complicating the issue further is the lack of accurate tests to properly identify infections, particularly those in early development.

Impact on Canadian Cattle Herds

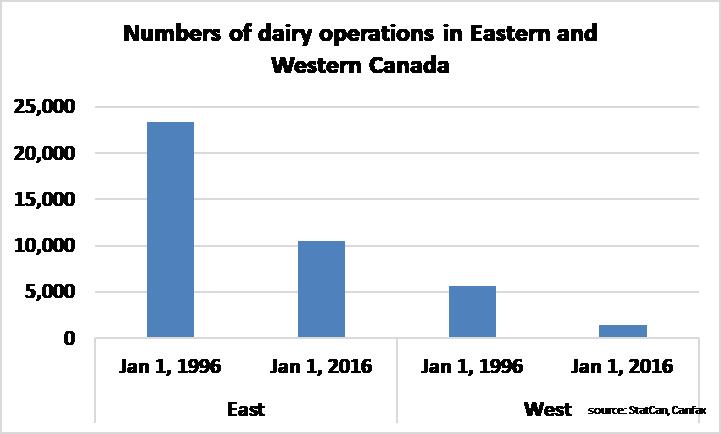

Researchers estimate that from 1 to 2% of mature Western Canadian beef cows (5% of herds) and 2 to 9% of Canadian dairy cows (and 70% dairy herds) may be infected with Johne’s disease. The higher incidence rate in dairy herds may be related to differences in calf management and because beef cattle generally range over larger areas and have less exposure to other cattle’s feces than dairy cattle. However, dairy cattle are important to the beef industry because most end their careers as lean beef.

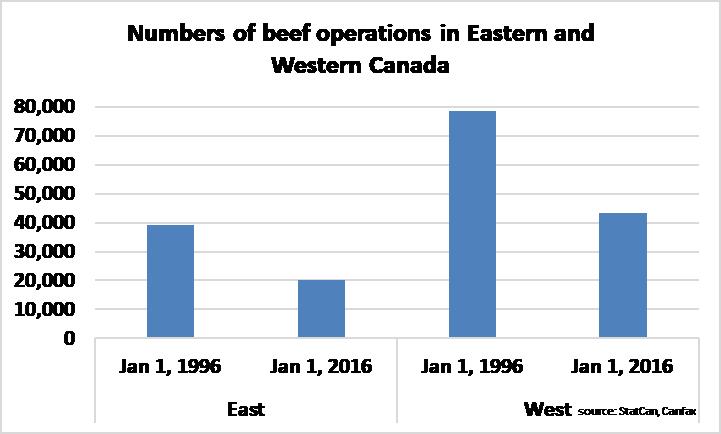

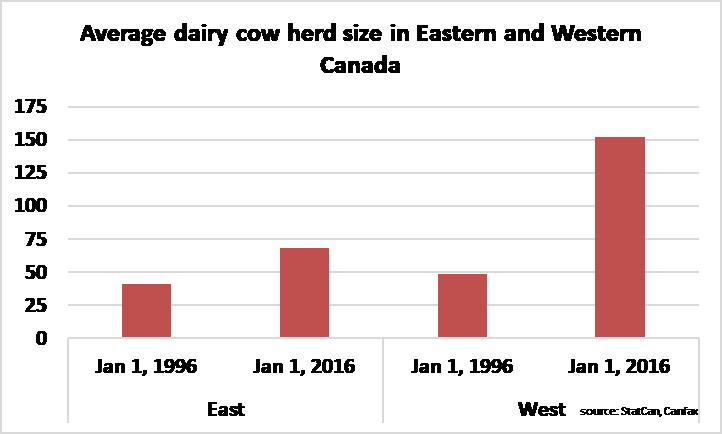

The rate of Johne’s disease appears to be increasing in both dairy and beef herds. This increase is likely linked to a clear trend towards fewer but larger beef and dairy herds in Eastern and Western Canada over the past 20 years.

Cows with Johne’s disease have been shown to wean calves that weigh 50 pounds less than normal herd mates.

Johne’s disease is costly. In addition to economic losses due to early culling of infected cows, data from nearly 5,000 beef cows in the US National Johne’s Disease Demonstration Herd Project found that calves from Johne’s positive cows weighed an average of 50 pounds less at weaning than calves from Johne’s negative cows. This production loss often goes unnoticed. The disease also affects reputations and economic margins in purebred operations selling bulls and replacement females, increases feed costs and reduce animal longevity.

Infection

Infection with MAP is thought to predominately occur when calves are less than 6 months of age but animals in infected herds probably receive multiple doses of MAP. It is estimated that only 1/3 of young animals with a single exposure to MAP will develop chronic infections. Research has also demonstrated that as cattle get older, a larger dose of MAP is required to cause infection.

Calves are commonly infected through ingestion of MAP in contaminated feces, puddles, milk or colostrum.

Calves are commonly infected through ingestion of MAP in contaminated feces or manure (from the ground or udder), puddles in the calving grounds or nursery pastures, or milk or colostrum from infected cows. MAP has also been found in the reproductive tract of infected animals but the risk of sexual transmission is believed to be extremely low.

Several environmental factors affect the survival of MAP. MAP does not multiply in the environment, but it can survive for over a year, even through Canadian winters. It is also very difficult to kill with common disinfectants and heat (both pasteurization and cooking).

Symptoms

Although infection usually occurs during early life, clinical signs do not appear until much later. The onset of clinical signs most commonly occurs between 2 to 6 years of age. The amount of MAP and age at infection are considered to be the two main factors that determine when clinical signs appear. Many infected cattle will shed MAP through their manure, potentially for many months or even years, before showing any signs of infection.

Once clinical signs appear, they are characterized by periodic to persistent diarrhea and progressive weight loss, both of which are non-responsive to treatment. An increased appetite may occur initially, but usually progresses to anorexia. In time, animals become very thin, weak and lethargic, and if not culled they will become too weak to stand, lie down and die.

Vaccination, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Diagnostic tests are unreliable for detection of pre-clinical infection in individual animals, there is no vaccine available in Canada, and there are no effective drugs for treatment of Johne’s Disease. Prevention is key.

There is no vaccine currently licensed or available in Canada as they interfere with tuberculosis testing and have limited efficacy.

Animals that have chronic diarrhea that doesn’t respond to treatment, and that are continuously losing weight and body condition even though their appetite is normal are likely to be shedding MAP and spreading Johne’s disease.

The diagnostic tests that are currently available do not reliably detect many infected animals until they have developed clinical signs of disease and are shedding large numbers of MAP. As a result, most efforts to eliminate Johne’s disease using “test-and-cull” methods have had limited success. By the time an animal is confirmed to be infected, it has had the opportunity to spread the infection to other susceptible animals in the herd.

Similarly, there are no effective drugs for treating cows with Johne’s disease; antibiotics licensed for use in cattle do not kill MAP. Controlled release monensin (Kexxtone™), has a label claim for the reduction in fecal shedding of Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP) in mature dairy cattle in high risk Johne’s disease herds and may be one part of a Johne’s control plan.

The beef and dairy industries continue to invest in research to develop better vaccines and detection methods, because effectively overcoming these shortcomings would greatly improve our ability to combat the disease effectively.

Prevention and Control

There is no quick-fix for Johne’s disease. Preventing and reducing Johne’s disease requires a combination of management practices to avoid introducing infected cattle, colostrum or manure into the operation, and calving, feeding and grazing management practices that reduce the risk that young calves will consume infected manure and colostrum. The worst mistake a producer can make is to separate a Johne’s infected cow and keep her in the calving area in hopes that she will gain weight before being sold.

Producers should work with a trained veterinarian to examine the herd’s Johne’s disease history, conduct a risk assessment of current management practices related to the spread of MAP, and develop a plan to implement the most appropriate measures to minimize Johne’s disease in that particular herd. Recommendations for herd testing and disease management will vary depending on how many animals are impacted, your herd size, whether you are seed stock producer, and the relative intensity of herd management. Contact your veterinarian for access to Johne’s tests and an effective testing protocol for your operation.

Preventing Johne’s disease has broad benefits. Management changes that decrease the risk of Johne’s disease will also reduce exposure to other, more common calfhood diseases (particularly calf scours), improve the effectiveness of vaccines for calfhood diseases, and improve overall herd health, performance and efficiency.

To prevent the spread of Johne’s disease:

- Do not buy Johne’s Disease: Purchase replacement animals only from test negative herds. When this is not possible assess herd status through owner and veterinarian statements.

- Do not borrow Johne’s Disease: dairy colostrum is more likely to contain Johne’s disease than beef colostrum. Do not “borrow” colostrum if you are unsure of a herds Johne’s disease status.

- Only purchase commercial colostrum supplements from a company that uses production methods that destroy MAP (ie. the Saskatoon Colostrum Company)

- Avoid exposing calves to potentially infected manure as much as reasonably possible: Responsible management of stock water, grazing, manure, and runoff can further reduce the possibility of spreading Johne’s disease to other cattle, neighbouring herds, wildlife and the environment. Once calves are weaned, do not put them on pastures used by cows.

- Calve first-calf heifers in a separate location from mature cows. First-Calf heifers are less likely to be shedding and calving them separately will protect their calves from being infected by mature cows.

- Bed generously when calving in confinement or muddy conditions.

- Keep the calving area clean at all times and maintain a low cow density in these areas. Calves on pasture if weather and facilities allow and restrict access to contaminated standing water if possible.

- Reduce manure build-up of pens and pastures where late-gestation cattle are kept. As soon as cows and calves have bonded, move cow-calf pairs to clean pasture.

- Avoid exposing calves to manure build-up by frequently moving location of feedbunks, waterers, and creep-feeders.

- Use separate equipment for handling manure and feed.

- Do not spread manure on land used for grazing, esp. for young stock.

- Cows that show symptoms of Johne’s disease should be removed from the breeding herd.Ionophores may reduce MAP shedding and reduce the risk that new animals will become infected.avoid overgrazing to reduce the risk that cattle will graze close to the ground and consume soil or manure.

- Daughters born before their mother began to show symptoms are at a lower risk of infection, but can be targeted for intensive diagnostic testing.

- Daughters born after their mother showed clinical signs were likely infected through colostrum and should be removed from the breeding herd.

- The role of wildlife is very unclear, but one study suggests that having dogs that keep wildlife off the yard reduced the likelihood of MAP infection.

Johne’s Testing Decision Tool

The Johne’s Testing Decision Tool was developed by a team led by Dr. Cheryl Waldner, the NSERC/BCRC Industrial Research Chair in One Health and Production-Limiting Diseases at the University of Saskatchewan. This interactive tool was designed to help producers and veterinarians evaluate various testing scenarios and options to get a clearer picture of what a management program can look like for their herd.

Previous webinar

The economic cost of Johne’s disease can be significant due to reduced weaning weights, later breeding, and losing or culling cows before they have recouped their production costs. Testing is challenging but can be a tactic to prevent these losses. This webinar reviews our new online interactive tool to inform producers and veterinarians on Johne’s disease testing options in cow-calf herds.

Speakers:

- Dr. Cheryl Waldner

- Dr. Leigh Rosengren

Relation to Crohn’s Disease

Johne’s disease has distinguished itself as a disease of importance not only due to the economic losses associated with limiting production on-farm and world trade, but also as a potential threat to human health. The symptoms of Johne’s disease in cattle are similar to those of human Crohn’s disease, and MAP has been isolated from some Crohn’s patients. This has led some scientists to suspect that MAP may play a role in both diseases. Other scientists argue that patients who are severely ill with Crohn’s disease are more susceptible to infection by many other organisms, including MAP. This argument has not been settled by the scientific community. No causal relationship between MAP and Crohn’s disease has been found.

To the best of our knowledge, neither the World Health Organization nor any individual nation has declared Johne’s disease to be zoonotic (a disease that can impact both animals and humans). In spite of this, misinterpreted and misguided information can have serious consequences for the beef industry.

Future Research Considerations

While much research has been conducted to understand MAP and Johne’s Disease, much of it has been done on dairy cattle. Further research specific to the beef industry will better enable producers to develop effective and efficient control programs and reduce any negative impacts MAP has on affected farms and on the entire industry.

- Learn More

-

To learn more on this topic, see the fact sheets posted on the right side of this page. External resources are listed below.

Literature Review of Johne’s Disease in Beef Cattle [PDF]

Steven Hendrick, DVM, DVSc and Dale Douma, DVMCanadian Johne’s Disease Initiative Brochure

Canadian Animal Health CoalitionCanadian Beef Cattle On-Farm Biosecurity Standard Implementation Manual

Canadian Food Inspection AgencyJohne’s Information Central

National Institute for Animal AgricultureJohne’s Education and Managment Assistance Program

Johne’s Information Centre

University of Wisconsin

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Steve Hendrick, consulting veterinarian at Coaldale Veterinary Clinic and Dr. Cheryl Waldner Professor, Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan for assisting with this page.

Ce contenu a été révisé pour la dernière fois en Juillet 2019.