On This Page:

- When Does Cold Stress Occur for Beef Cattle?

- Cattle Response to Cold Stress

- Impact of Cold Stress on Beef Cattle Energy Requirements

- Importance of Weather Protection

- Winter-Feeding Strategies

- Extended Grazing Considerations for Beef Cattle

- Feeding Hay, Silage and Other Stored Forages to Beef Cattle

- Winter Management Considerations

- Beef Cattle Body Condition

- Water Access for Beef Cattle

- Forage and Feed Quality for Beef Cattle

- Cattle Nutrient Requirements

- Impact of Mycotoxins

- Using Alternative Feeds for Beef Cattle

- Parasite Management

Many regions of Canada experience extended periods of cold weather during the year and these environmental conditions present challenges for efficiently and profitably raising beef cattle. Understanding the impact cold stress can have on the health, welfare and performance of cattle is important, along with implementing management practices to lessen the impact.

Beef cattle are fed over winter using a variety of methods. The complexity and mechanization will be unique to the individual operation and management goals. However, the overall objective is to maintain cows in good body condition so they remain healthy and productive even in the coldest of conditions.

| Key Points |

|---|

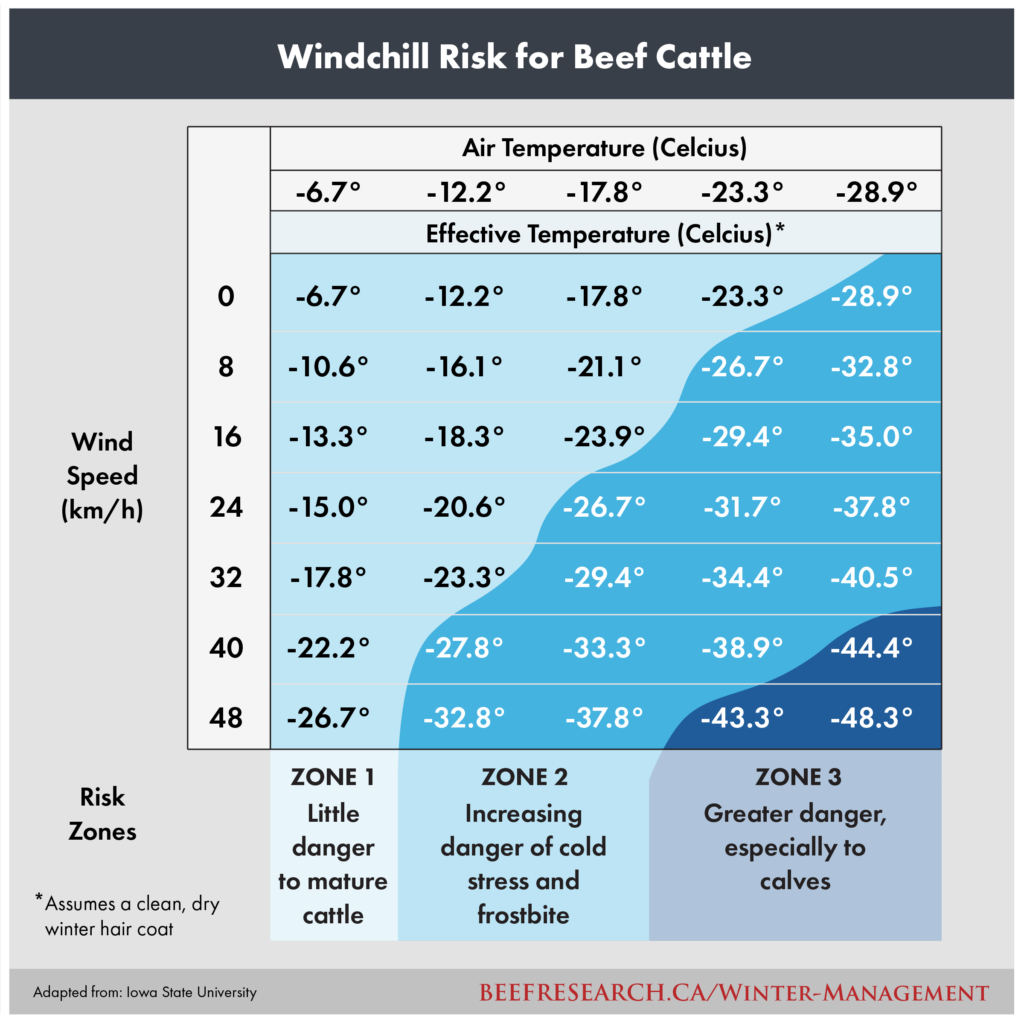

| Cattle experience the effective temperature, which is a function of both air temperature and windchill. |

| Cold stress occurs when the effective temperature drops below the lower critical temperature (LCT). |

| When experiencing cold stress, cattle can increase feed intake anywhere from 2-25%, depending on weather conditions and feed availability. |

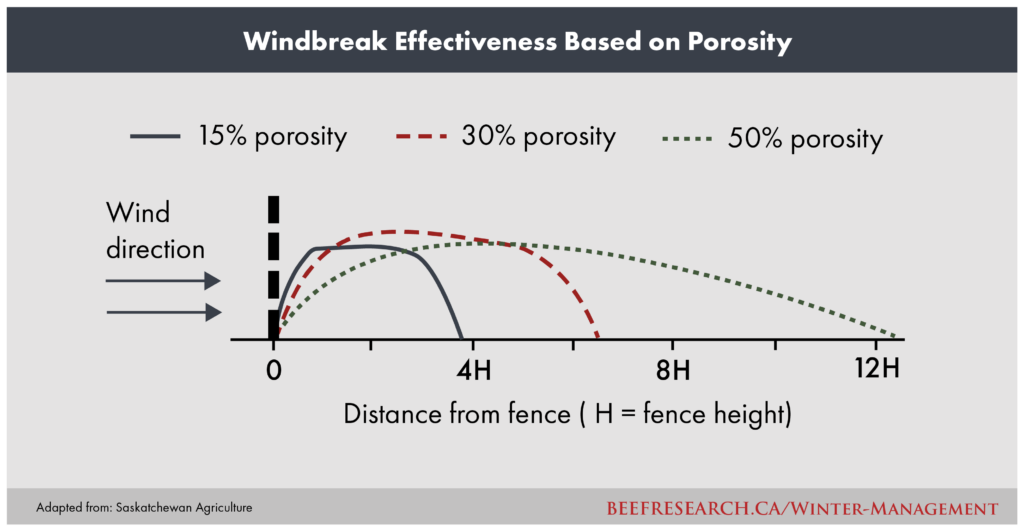

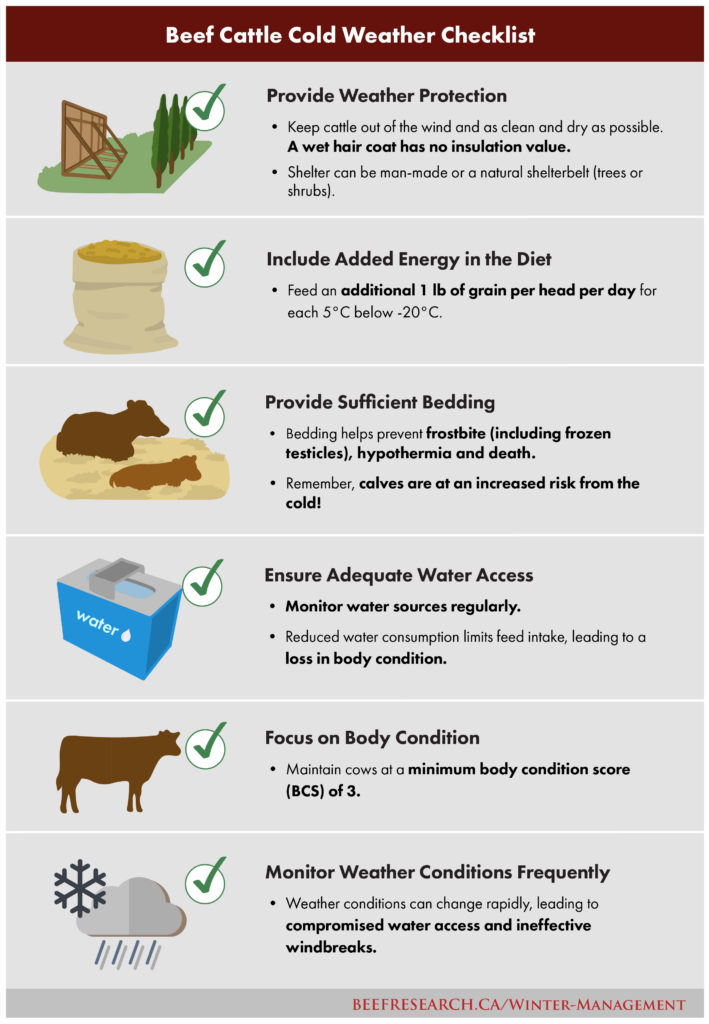

| The maximum amount of protection from a windbreak is obtained with a fence porosity of 25-33%, with the protected area being eight to ten times the height of the fence. |

| A rule of thumb is to provide an extra 1 lb (0.45 kg) of grain or pellets per day for every 5 degrees the temperature is below -20 degrees Celsius at midday. |

When Does Cold Stress Occur for Beef Cattle?

Cattle experience what is called the effective temperature, which is a function of both air temperature and windchill. The relationship between effective temperature and wind chill is illustrated in the below figure. Heat loss is greater as wind speed increases due to cool or cold wind drawing heat away from the animal much quicker than still air at the same temperature.

Cold stress occurs when the effective temperature drops below the lower critical temperature (LCT). This is the temperature below which cattle in good body condition will begin to experience cold stress and their metabolism increases to keep themselves warm. Table 1 shows the estimated LCT for mature beef cattle with varying coat conditions.

Table 1: Estimated Critical Temperatures for Beef Cows

| Coat condition | Estimated lower critical temperature (Celsius) |

|---|---|

| Summer coat | 15 |

| Wet coat | 15 |

| Dry, fall coat | 7 |

| Dry, winter coat | 0 |

| Dry, heavy winter coat | -8 |

Note: The above table estimates the lower critical temperature for beef cows in good body condition assuming no wind chill or health conditions.

The LCT will vary depending on several conditions, including age of the animal, body condition, wind speed, environmental temperature, moisture and the animals’ coat conditions. For example, in the warm summer months, a beef cow with a clean, dry haircoat has an estimated LCT of 15°C. This same cow would have an LCT of 0°C in the winter, which means she is now experiencing cold stress at temperatures below 0°C. However, if her winter hair coat loses its insulating ability because it is wet or matted with manure, the LCT rises to 15°C, and she will experience cold stress more quickly.

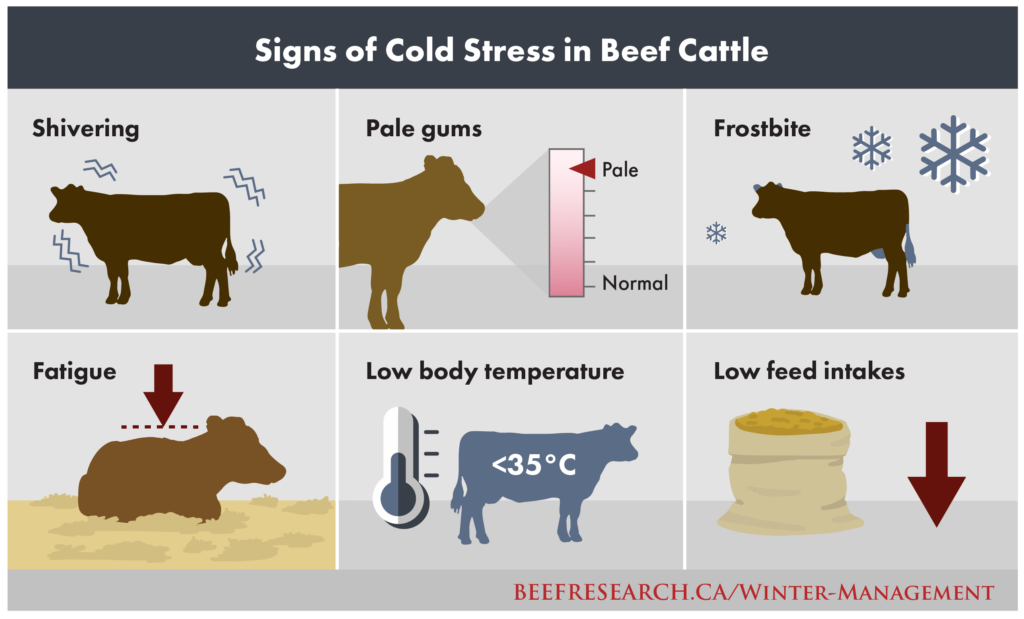

Cattle Response to Cold Stress

Cattle can acclimate themselves to cold weather through increased thermal insulation (hair coat) and regulating the amount of heat produced through normal digestion and metabolism, which means additional feed must be provided. An increase in feed intake can typically meet the added energy required for maintenance during cold stress. Intakes can increase anywhere from 2-25%1, depending on weather and feed availability. However, under extreme cold conditions, cattle cannot consume enough feed which results in a negative energy balance, meaning that the cows will now utilize body reserves to generate heat.

Table 2: Impact of Temperature on Beef Cattle Feed Intake

| Temperature (Celsius) | Increase in Feed Intake (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| 15 to 25 | No impact of temperature |

| 5 to 15 | Increase of 2 to 5% |

| -5 to 5 | Increase of 3 to 8%* |

| -5 to 15 | Increase of 5 to 10% |

| <-15 | Increase of 8 to 25%** |

*Any sudden drops in temperature may cause digestive upsets in young stock. **Intakes during extreme cold conditions will vary greatly. Intake of high roughage feed may be limited by bulk.

If additional good quality feed is not provided or available, cows will begin to lose weight. The more weight cows lose, the more susceptible they are to cold stress and losing additional condition. Cows and heifers that calve in poor body condition, and in the winter months, are at an increased risk of cold stress. If severe enough, death losses can occur due to hypothermia.

Impact of Cold Stress on Beef Cattle Energy Requirements

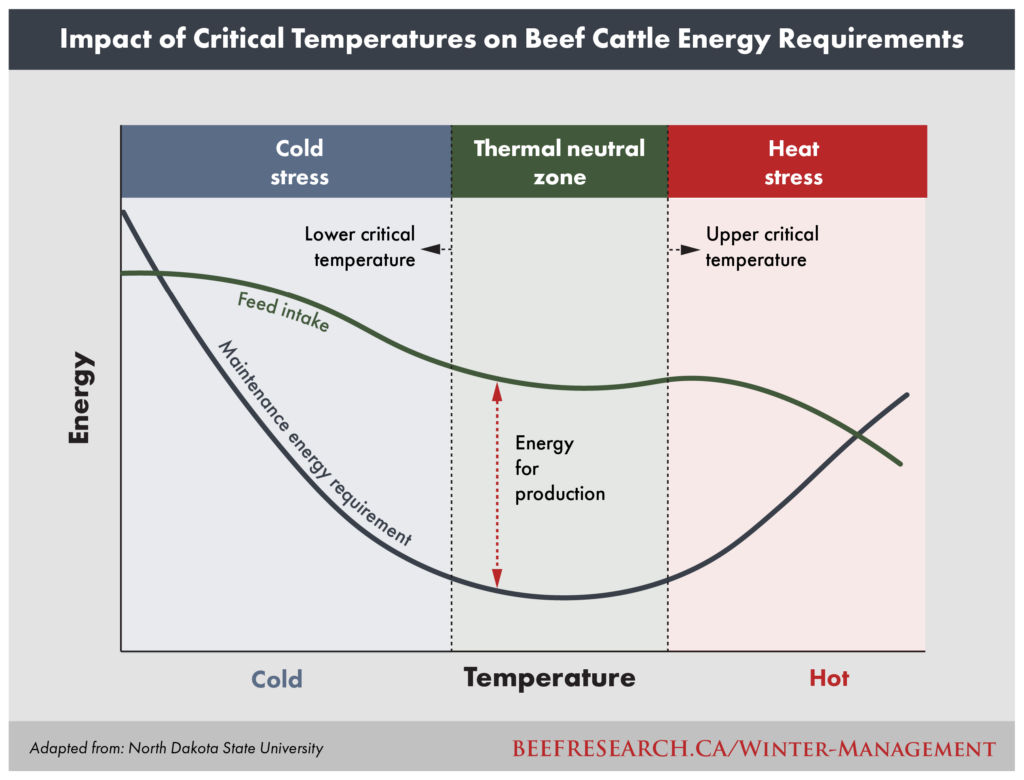

Cold stress impacts beef cattle nutrient requirements by increasing the need for energy. These requirements increase as the temperature drops below the lower critical temperature (LCT). The additional energy needed can either be provided through feed or body reserves.

Feeding programs should be adjusted in prolonged cold conditions to provide added energy. It is generally accepted that energy requirements increase by 2% for every degree the temperature drops below the LCT.

Adjustments can be made to utilize feeds that will supply additional energy but DO NOT rapidly change the diet as this can result in rumen upsets. Providing high-quality forages can be sufficient for cows in good body condition. However, during extreme cold weather or for underconditioned cows, adding a concentrate source to the diet is recommended. A rule of thumb is to provide an extra 1 lb (0.45 kg) of grain or pellets per day for every 5 degrees the temperature is below -20 degrees Celsius at midday. This means that a beef cow exposed to a temperature of –30°C requires a minimum of 2lbs additional grain.

A rule of thumb is to provide an extra 1 lb (0.45 kg) of grain or pellets per day for every 5 degrees the temperature is below -20 degrees Celsius at midday.

Depending on forage quality or the group of cattle being fed, additional protein supplementation may also be necessary. Adequate protein promotes fiber-digesting bacteria in the rumen, which increases forage digestibility leading to increased feed intake and a higher energy yield from the diet.

Work closely with a nutritionist or utilize ration-balancing software programs, such as CowBytes, to balance supplementation with your forage base and ensure the nutrient requirements of your herd are being met.

Importance of Weather Protection

The success of a livestock operation during the winter months is influenced by the shelter provided. Depending on the geographical location, protection from wind and snow is not always readily available. In these situations, construction of man-made windbreaks is necessary.

The effectiveness of a windbreak is only as good as the design chosen, which is determined by factors such as number of animals utilizing the structure and the prevailing wind direction(s). A general recommendation is one foot of fence length for each cow.

Livestock windbreaks should be porous and can be constructed as permanent or temporary (portable) structures. The maximum amount of protection is obtained with a fence porosity of 25-33%, with the protected area being eight to ten times the height of the fence.2

In addition to wind protection, adequate bedding should be provided in all areas where cattle sleep as well as calving areas. Bedding provides a layer of insulation between the cold ground and snow and the animal, which is crucial to help prevent frostbite (including frozen testicles or teats), hypothermia and death. It also works to keep cattle dry and free from mud accumulation, both of which reduce the insulating properties of cattle hair coats thus increasing feed requirements. It frostbite damage is observed on the scrotum, it is recommended to complete a Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluation (BBSE) prior to the breeding season.

Calves are at an increased risk from the cold. Calf warming areas and adequate colostrum should be prepared ahead of any expected periods of extreme cold weather conditions.

Winter-Feeding Strategies

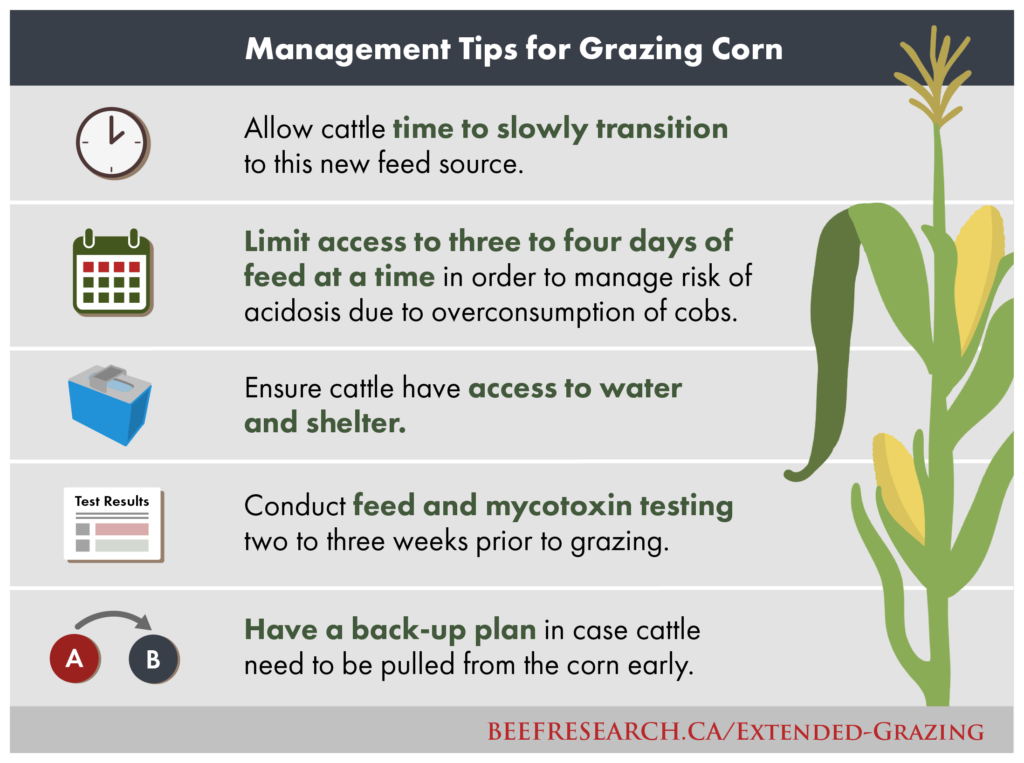

Extended Grazing Considerations for Beef Cattle

Methods to extend the grazing season (including stockpiled perennial forages, use of annual forages, crop residues and bale grazing) have considerable economic and environmental benefits over traditional winter-feeding systems. However, for any type of extended grazing system to be successful, good management is needed to keep cattle healthy and in good body condition. Although it is possible to use multiple methods to achieve production goals, not all systems are recommended for all regions due to timing of rainfall, amount of rainfall or snowfall and type of snowfall.

Learn more about different methods of extended grazing and which system might fit your operation by visiting the BCRC’s Extended Grazing webpage.

Learn more about fencing requirements for extended grazing systems with Pasture 101.

Feeding Hay, Silage and Other Stored Forages to Beef Cattle

The objective of stored forage is to preserve resources at their peak quality in the summer months in order to provide winter feed for livestock when grazing is limited. It is essential to harvest forage at the appropriate time, based upon nutritional quality, forage yield and climatic conditions, and then to store it properly to reduce losses. Feed is the major input cost in cattle production; therefore, producers must evaluate the cost of production for all stored forage systems.

Learn more on the BCRC’s Stored Forages webpage.

Winter Management Considerations

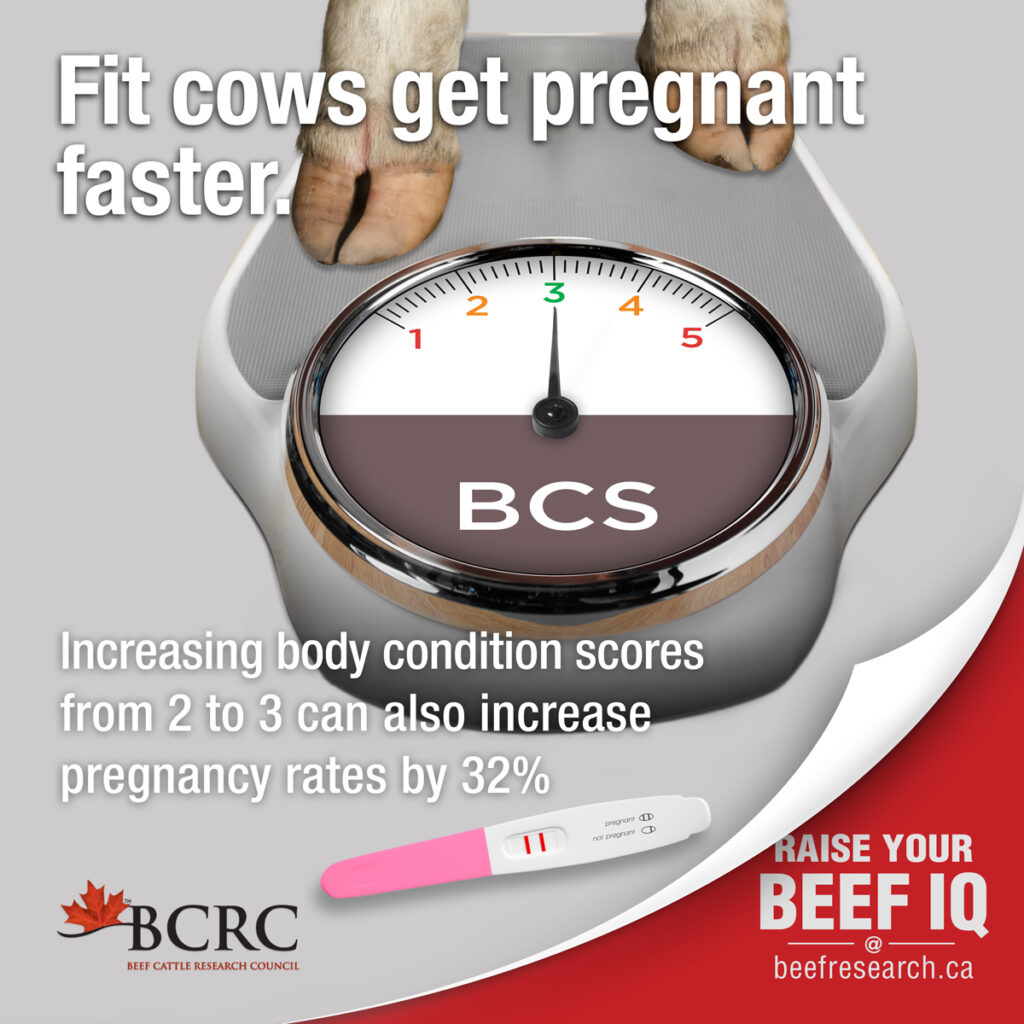

Beef Cattle Body Condition

Body condition at winter’s onset is a key determining factor in how well cattle will tolerate cold weather conditions. Thin cattle do not have fat reserves and require more feed than cows in good body condition in order for them to tolerate the cold winter months.

Learn more about body condition and how to score your cattle by visiting the BCRC’s Body Condition webpage.

Water Access for Beef Cattle

Inadequate access to water during cold weather will limit feed intake and reduce the cow’s ability to meet its energy requirements. There are many different water systems available and the suitability of each will depend on a number of factors, such as herd size, water sources, access to power, local geographic conditions and cost.

Snow is not always a reliable water source. It is not always there, it is not always clean, and sometimes it is frozen too hard for cattle to eat.

Learn more by visiting the BCRC’s Water Systems for Beef Cattle webpage.

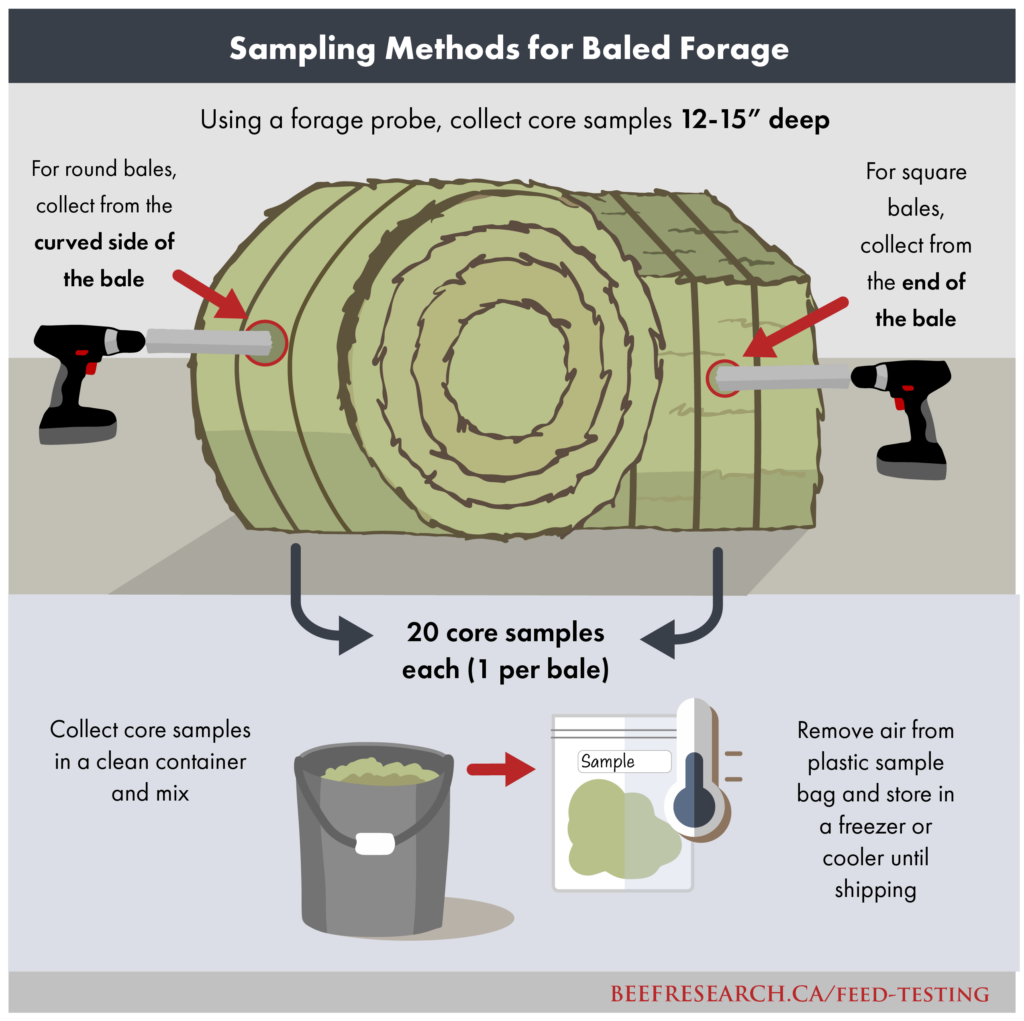

Forage and Feed Quality for Beef Cattle

When the quality of the feed and forages are unknown, the ability to maintain animal health, welfare and productivity becomes significantly more difficult, particularly during the colder months of the year. Feed testing is an important tool when tackling feed management and allows producers to economize and prioritize feed use.

Learn more by visiting the BCRC’s Feed Quality, Testing and Analysis for Beef Cattle webpage.

Cattle Nutrient Requirements

Across all sectors of the beef cattle industry, feed quality, cost and efficient digestion/absorption/conversion are key factors in animal health, reproduction, performance and profitability.

Nutrient requirements will differ depending on the animal’s class, age, condition and stage of production. Group animals based on their stage of production to allow for efficient use of forages and other feeds. Energy is typically the limiting nutrient in winter rations, followed by protein.

Learn more about beef cattle nutrient requirements on the BCRC’s Nutrition in Beef Cattle webpage.

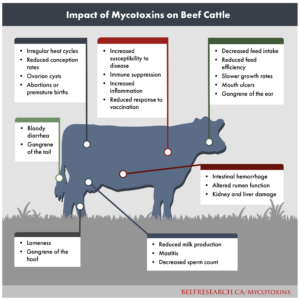

Impact of Mycotoxins

Often a hidden hazard in beef cattle diets, mycotoxins are a group of harmful toxins produced by certain types of fungi, including mold. Virtually all feeds that are fed to beef cattle are potential sources of mycotoxins, including pastures, cereal swaths, standing corn, ensiled forages, co-products and commercial feeds.

Learn more about the impact of mycotoxins and how to test for them in your feed by visiting the BCRC’s Mycotoxin webpage.

Using Alternative Feeds for Beef Cattle

On most cattle operations, feed represents the largest single variable cost. Livestock producers continually examine ways to reduce this cost and explore options to efficiently and safely feed their livestock. Alternative or non-conventional feeds can be a flexible, low-cost option, but feed testing is recommended to ensure nutritional requirements of the groups of cattle being fed are met.

Learn more on the BCRC’s Alternative Feeds webpage.

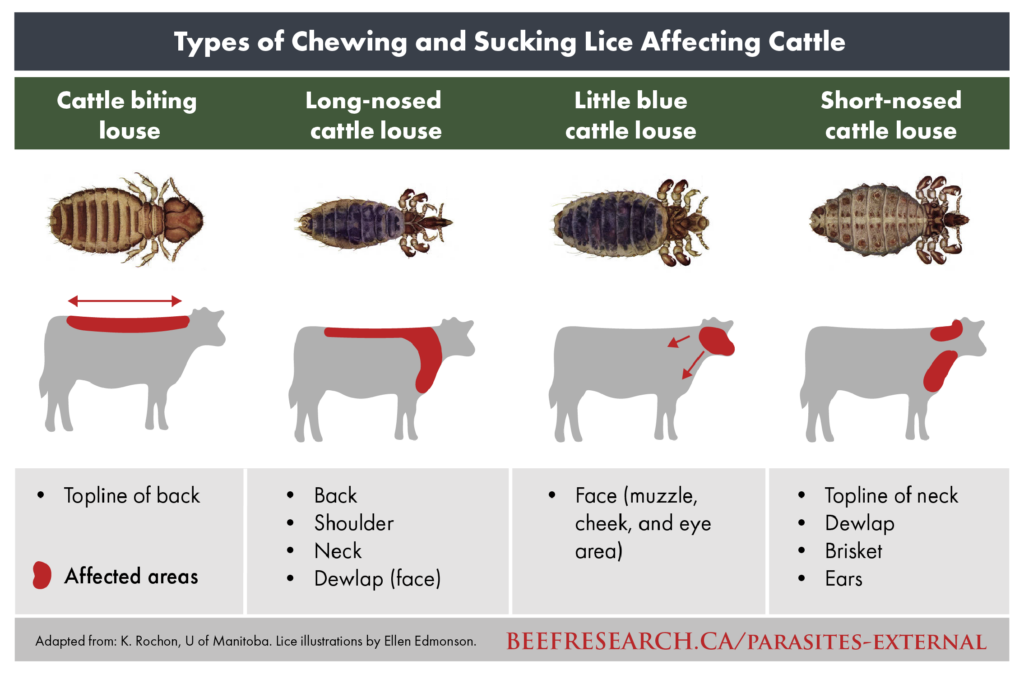

Parasite Management

Both internal and external parasites can lead to stress, reduced weight gain, decreased milk production and other production losses, irritation, and injury in their host animal. Parasites can also alter grazing and feeding behaviour in beef cattle. Developing an effective parasite control plan prior to winter feeding can help to reduce parasite loads the following spring.

Learn more on the BCRC’s Internal and External Parasites webpages.

- References

-

1. NRC, 1981. Effect of Environment on Nutrient Requirements of Domestic Animals. National Academy Press, Washington, D. Available online.

2. Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture. Portable Windbreak Fences. Available online.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca.

This content was last reviewed December 2024.